I have a confession to make… inside my normie, North Face-wearing exterior, I have the soul of a stone cold goth girl.

I don’t know why I don’t show it more: I never mastered the makeup; I usually scramble out the door and opt for comfort over style; Doc Martens hurt my feet. Whatever the reason, my inner goth doesn’t get to express herself as much as I’d like — but I’m very secure in the fact that she exists. She’s in the flowy black lace dress hanging in my closet, in the dark themes of my art and, most importantly, in my study of Jewish text (what?)

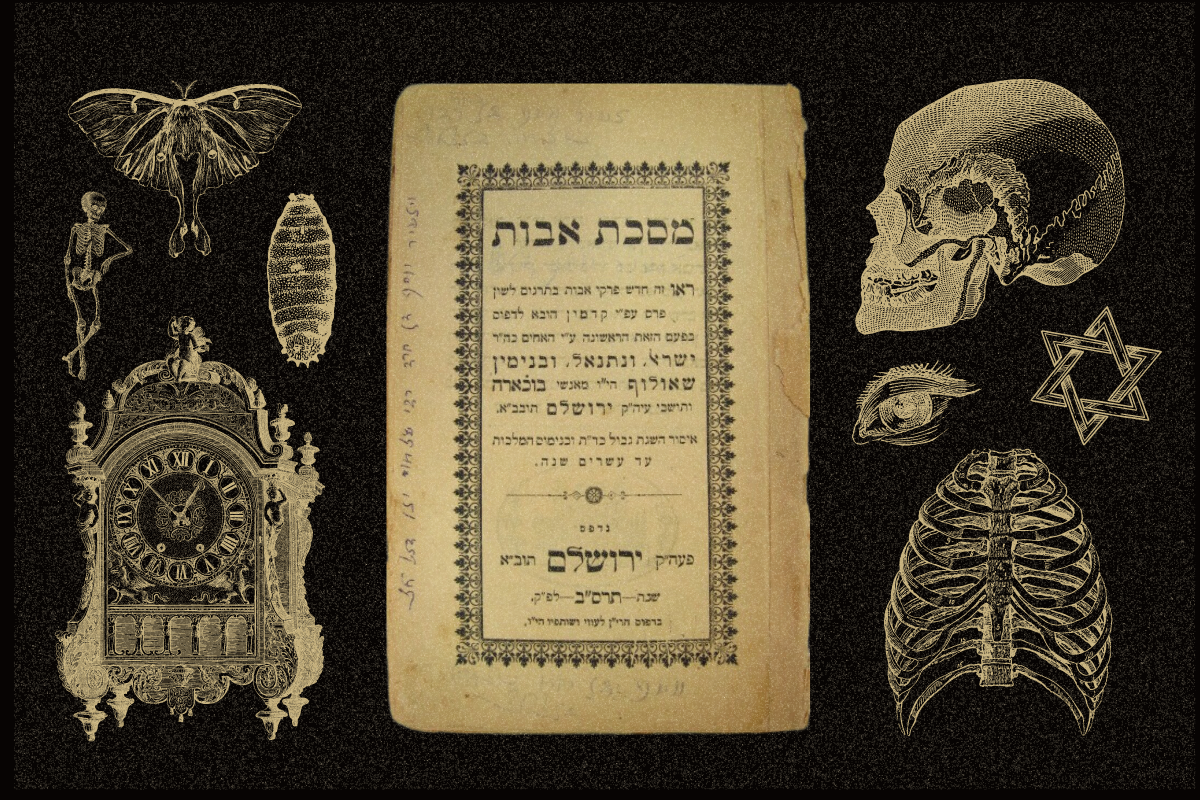

That’s right — I believe studying Jewish text can be a powerful practice for flexing those goth muscles. I am thinking especially of the most goth text of all: Pirkei Avot.

Pirkei Avot, or ethics of the fathers (also translated as chapters of the ancestors), is a section of the Mishnah (the Jewish code of law). Unlike the rest of the Mishnah, it records no arguments, only advice, quips and zingers about how to live a moral life. It was my entry into Jewish study because of its accessible nature. Pirkei Avot is also seasonally appropriate because it is traditionally read between Passover and Shavuot as a practice for preparing to receive the Torah. I find it a meaningful way to add ritual and focus to this period of time. It forces me to think hard about what it means to receive the Torah, a concept I find hard to grasp.

What makes Pirkei Avot “goth” is the vivid, dark imagery and dramatic statements it uses to drive home its messages.

For me, goth is the radical notion that death and decay can be beautiful. That when we hide from these concepts, we also hide from ourselves. That these concepts bring us closer to our emotions and what truly makes us human. That mortality isn’t scary… it’s style. Pirkei Avot also delivers in this area, using the same bold, in-your-face language that the goth aesthetic communicates visually.

Here are some of the most intense of those lines, complete with interpretation of how their particular “dark” take contributes to the power of the ethics behind them.

Hillel saw a skull (2:6): warning of consequences

“[Hillel] saw a skull floating on the face of the water. He said to it: because you drowned others, they drowned you. And in the end, they that drowned you will be drowned.” Pirkei Avot 2:6

The “gothness” of this passage is pretty straightforward… there’s a skull in it, an age old symbol of mortality. However, there’s also a deeper significance. The skull’s representation of death communicates a type of permanence in Hillel’s message. The drama of this passage emphasizes how critical our actions are to how we interact with, and are affected by, the universe. Commentary suggests that Hillel may have known the identity of the skull. This contributes to the fact that this skull was a real human whose actions lead to their death.

Know where you come from (3:1): a lesson in humility

“Akabyah ben Mahalalel said: mark well three things and you will not come into the power of sin: Know from where you come, and where you are going, and before whom you are destined to give an account and reckoning. From where do you come? From a putrid drop. Where are you going? To a place of dust, of worm and of maggot. Before whom you are destined to give an account and reckoning? Before the King of the kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed be he.” Pirkei Avot 3:1

Any guy who includes “maggots” in his legacy quote isn’t messing around. That’s a fellow goth right there! He knows the importance of decay as a lesson. That’s what makes this paragraph so powerful. It helps us visualize our beginning and end for what they truly are: metal A.F.! (Yet also small and insignificant.) I would imagine many Hey Alma readers may struggle with the concept of facing judgment, which is totally ok! For me, facing judgment isn’t necessarily coming before a big man with a beard, but rather a contemplation on what matters. To Akavya ben Mahalalel, it’s a reminder that we are small, and to behave accordingly — with humility.

Against your will (4:22): advice against apathy

“…let not your impulse assure thee that the grave is a place of refuge for you; for against your will were you formed, against your will were you born, against your will you live, against your will you will die, and against your will you will give an account and reckoning before the King of the kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed be He.” Pirkei Avot 4:22

Goth is tied into the beauty of decay for me, but it also has the tendency to be seen as a very apathetic movement. If death awaits us all, why bother with anything? This passage warns: Death is not a release. It is only the beginning of a much more terrifying prospect. The passage goes on to remind us that we are here against our will, but that only stresses the fact that we must be here for a reason. Here, I interpret “facing judgment” as a reminder of our legacy. What we do on this earth does have an impact, even if we don’t mean to be here and won’t be here forever. The image of death, the drama of it all, stirs us to action. This is a call for us to live intentionally.

What all these passages have in common (other than being very hardcore) is their emphasis on awareness — awareness of what it means to be alive. They reach that awareness through imagery that reminds us of our mortality. Pirkei Avot doesn’t shy away from the heavier burdens we carry as human beings, and that recognition adds to the power of the text. By looking at the text through the lens of my inner goth, I get to focus in on these powerful paragraphs and marvel at their gruesome beauty (because they are, if nothing else, extremely beautiful). The goth aesthetic is relatively new compared to the longevity of Torah study, but that means it provides a new and fresh look at a classic and precious text.

Most importantly, reading Pirkei Avot through a goth lens means truly accepting that the Torah comes to all of us. The things that make us different only enrich Torah study for everyone. Every Jewish person has something new and unique to bring to our ever-changing, ever-growing understanding of Torah. Even — and perhaps even especially — the goth ones.