On Nov. 7, 1968, a resolute Beate Klarsfeld made her way to the Christian Democrats Union (CDU) party conference on a singular mission. Her target was German Chancellor Kurt Kiesinger, a former member of the Nazi party.

With the precision of a skilled operative, Beate deftly distracted the security guard and navigated swiftly through the rows of politicians until she stood before Kurt Kiesinger. In an instant, she turned to the prominent CDU figure and delivered a stinging slap across his face, declaring with force, “Nazi, Nazi!” in front of the German and international press.

In the post-war years, many former Nazis had seamlessly reintegrated into the fabric of German society, often rising to distinguished positions within politics and the judiciary. Figures like Eduard Dreher became state prosecutors and influential figures in the Ministry of Justice, while high profile members of the SS like Klaus Barbie, who evaded prosecution for decades, utilized a clandestine network known as ‘the ratline’ to flee to South America and forge new lives far from the reaches of their past atrocities.

Kiesinger himself had served within the Reich’s foreign ministry’s propaganda arm, producing war propaganda and heavily anti-Jewish material, even after learning about the extermination of Jews in concentration camps. Fast forward 21 years, and he had ascended to the highest level of public office in West Germany, becoming the Federal Chancellor.

The slap Beate delivered eventually reverberated around the world and set off a chain of events where she and her husband Serge would bring numerous Nazi war criminals and collaborators to justice.

Beate (pronounced bey-ah-tah) Auguste Künzel was born on Feb. 13, 1939, in Berlin, just before the advent of World War II. In an interview with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, she described her upbringing as that of “a typical German family, not members of the Party, but they belonged to the silent majority when Hitler came to power and voted for him.” Like most able-bodied German men at the time, her father was conscripted to fight in the war. Beate’s early memories included the time when Germans were displaced from the Eastern territories, where refugee camps were established. In these camps, children were made to salute “Heil Hitler” and sing Nazi songs in kindergarten. Reflecting on those days, she recounted, “It was a hard time because we had not enough to eat.” However, she also added, “There was a time to play, we were children. I was not Jewish, so I had no problems.”

Her husband, Serge was born to an assimilated Jewish family in Bucharest, Romania, in September 1935. The horrors of World War II overshadowed Serge’s early years, although he humorously recalled being the war’s first casualty after falling down the stairs and getting a wound above his eye, just minutes after France declared war on Germany.

In 1943, when he was 8 years old, Serge, his mother and his sister huddled together behind a false wall in their home in Nice to evade capture during a roundup; his father Arno, was arrested by the Schutzstaffel (SS). Tragically, Arno Klarsfeld was subsequently deported to Auschwitz, where he died.

Serge and Beate’s paths crossed in the spring of 1966, at the Alliance Française language school in Paris, setting the stage for a friendship that quickly blossomed into romance. Beate later articulated that Serge played a crucial role in her transformation into “a German of conscience and awareness.” Reflecting on the deep bond they shared, she said:, “I gave him what he hoped for — I became the German who chose to act.”

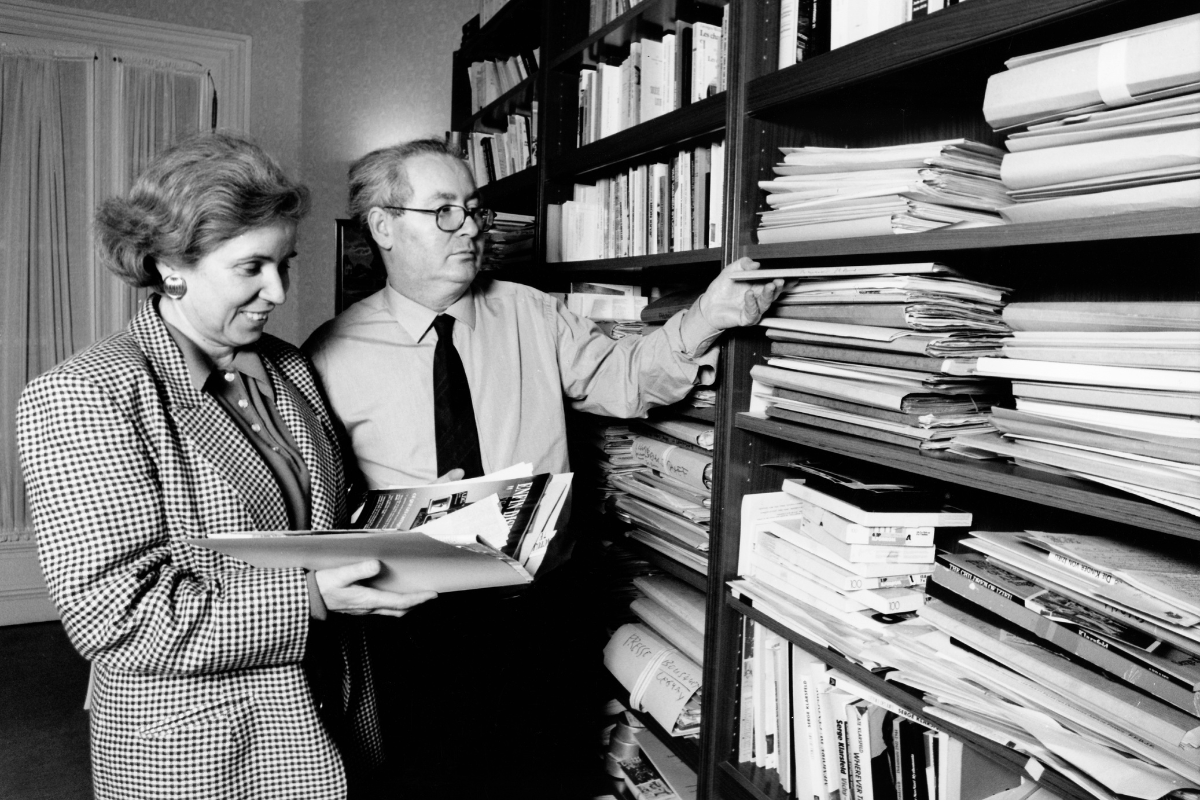

Their work, marked by meticulous research, unyielding determination and occasionally questionable ethics (all in the name of the greater good), brought numerous war criminals to justice and served as a powerful reminder of the importance of memory and justice in the face of history’s darkest chapters.

Here are a few high-profile Nazis and collaborators the Klarsfelds helped bring to justice.

Klaus Barbie

Barbie, known as the notorious “Butcher of Lyon,” epitomized the chilling efficiency of Nazi brutality. As the Gestapo chief in Lyon, Barbie orchestrated the deportation of 7,500 Jews and the execution of 4,000 resistance fighters.

Post-war, he deftly slipped through the fingers of justice by working with U.S. intelligence and later fleeing to Bolivia under the alias Klaus Altmann. There, he was involved in arms dealing and ascended to the rank of lieutenant colonel within the Bolivian Armed Forces. Barbie is credited with playing a role in the Bolivian coup of 1980, helping install the dictator Hugo Banzer, to whom he worked as a close advisor, interrogator and torturer.

The Klarsfelds revealed his whereabouts in Bolivia in 1971 and initially attempted a kidnapping akin to that of Adolf Eichmann in 1962 (after a tireless public campaign came to no avail) but this failed due to a car accident. After the Tejada dictatorship fell three years later to the socialists, with whom the Klarsfelds had established rapport, Barbie lost his protection, leading to his extradition to France. In 1987, Klaus Barbie was convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Kurt Lischka

Lischka, a high-ranking SS officer and Gestapo chief, was deeply complicit in the horrors of the Holocaust. In Germany, he was responsible for overseeing the mass deportations of German Jews following the devastating events of Kristallnacht. He then facilitated the deportation of over 20,000 Jews from Berlin to the eastern border, where countless individuals succumbed to starvation or exposure — a grim outcome that one of his superiors disturbingly referred to as “ingenious.” As the Gestapo head in Paris, Kurt Lischka coordinated the deportation of 73,000 Jews to concentration camps.

Despite being sentenced to life imprisonment in absentia by a French court, he lived freely in West Germany for decades, incongruously holding an executive position at a shipping company. After campaigning for Lischka’s extradition came to no avail, the Klarsfelds organized another kidnapping attempt. This time, they enlisted the help of a political scientist, a photographer and an Orthodox Jewish doctor, forming a determined five-member team to bring Lischka to France.

He was a creature of habit. Beate spent days covertly tracking Lischka, meticulously noting his movements: which tram he took to work, his schedule, and his return to the office. Meanwhile, the others were responsible for covertly bundling him into their getaway car.

When the abduction attempt failed, Beate took full responsibility and handed herself in to the Cologne prosecutor. She also gave him a thorough dossier detailing Lischka’s crimes, including his signatures on hundreds of deportation orders and anti-Jewish mandates, and explained why they were trying to bring him to France without official approval.

“Arrest me for attempted kidnapping,” she challenged the prosecutor, “and you’ll imprison a young mother while letting a Nazi remain free.” The prosecutor, unswayed, produced a warrant from his desk and placed her under arrest. She was subsequently tried and sentenced to two months in jail by a Cologne court.

This audacious strategy, however, had its impact. Beate’s arrest sparked outrage in Europe, providing her and Serge with a platform to highlight Lischka’s atrocities. Due to mounting public pressure, her prison sentence was commuted to probation.

Despite the intensifying public scrutiny, Lischka evaded justice until 1980. Only after sustained public campaigning was he finally convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Paul Touvier

Paul Touvier, a prominent figure in the Vichy Milice, was the first Frenchman to be convicted of crimes against humanity. As an important aide to Klaus Barbie, he was directly involved in the brutal executions of seven Jewish hostages in 1944, and played a crucial role in the persecution of Jews in Nazi-occupied France.

After the war ended, Touvier was sentenced to death in absentia twice for treason and collaboration with the enemy. Yet in a dramatic escape from a Paris police station in 1947, he managed to evade justice for more than four decades. Shielded by influential figures within the French political establishment and the right wing of the Catholic Church, Touvier, along with his wife and two children, found refuge in convents and monasteries across the country. Successive governments turned a blind eye, allowing the statute of limitations to lapse on most of his crimes.

His luck finally ran out in 1989 when police stormed a priory in Nice, where Touvier was hiding under an assumed name. Among his possessions, officers discovered Nazi memorabilia, including medals and decorations from the German army, further incriminating him.

Touvier was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1994. Among the prosecutors at his trial were Serge Klarsfeld, and Arno — the Klarsfeld’s son.