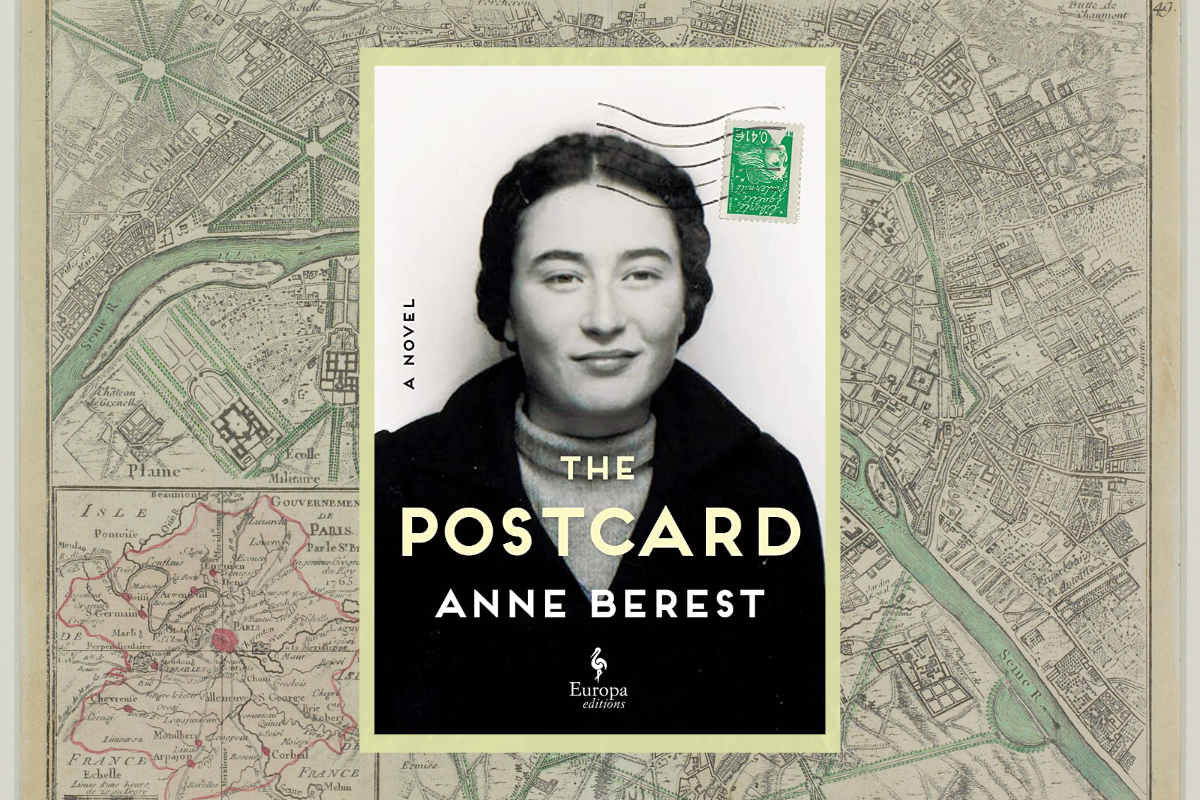

French author Anne Berest’s “The Postcard,” whose English translation is out today from Europa Books, tells the story of the loss and survival of Berest’s family during the Holocaust in Paris. But it starts with a postcard.

On a snowy January in 2003, a postcard arrives to Berest’s mother’s mailbox. On the front, a photo of the Opéra Garnier in Paris; on the back, four names: Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, Jacques — all family members who had died in Auschwitz. The postcard seemed quite ominous, given that the Opéra Garnier served as Nazi headquarters during the war. But it wasn’t until after Anne Berest’s young daughter experienced antisemitism in the schoolyard almost 20 years later that Berest, along with her mother, decided to find out who sent this postcard.

The story of the postcard is real from start to finish. The entire book is based on a real story, grounded in Berest’s and her mother’s lives as well as in the research they uncovered about their family. It’s been described as autofiction or autobiographical fiction, wherein some elements of the book are autobiographical, while others are based in fact, but fictionalized.

The resulting book is part family history, part mystery investigation and part search for Jewish identity. It’s an incredible work, a bestseller in France, and was recently awarded the first US Goncourt Prize Selection. Hey Alma talked with Berest about what it means to write a “true novel,” the role of chance in survival and how the book brought her closer to her Jewish identity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Why is this story so important to tell now?

Because the last witnesses and the last victims of the Holocaust are dying. Soon, no one will be able to say, “I was there.” No one will be able to say, “Listen to what I saw, what I went through.” For me, it means that this is a mission of our generation — what we call the third generation — to keep on going with the duty of memory.

I grew up in a world where the survivors of the Holocaust were alive and were very active. I remember when I was a pupil at school, they used to go to high schools to bear witness to tell us: Never forget. Never forget the gas chambers. Never forget the persecution of the Jews.

That’s why it’s so important — because we know that our children will not be contemporaries with victims [of the Holocaust]. We have to take over this job of speaking out.

How would you describe this book? Is it autofiction (which combines truth and invention)? How can autofiction feel truer than non-fiction?

I say that it’s a true novel. It’s written like a novel with Romanesque expression, in a very narrative style — part written like a detective story, part written like a family history. But the novel is true because it’s entirely based on true facts, based on events that happened to me and to my family. I didn’t imagine anything. To tell the truth, I didn’t have the imagination to invent what real life brought to me.

A French writer that I love, Françoise Sagan, said that art must take reality by surprise. But in my case, it was a reality that took me by surprise. What I was living and discovering during my investigation was crazy. So, to answer your specific question: Yes, it’s autofiction. But I prefer to call it a true novel.

How can autofiction make stories feel more true than nonfiction? That’s a very interesting question. I don’t have the answer. Maybe [it’s because you feel] the incarnation of the characters, the beating of their hearts, and maybe you can identify with them more.

Reading this story and thinking about other stories of the Holocaust, I’m struck by how much chance plays a role in our stories. How do you think chance plays a role in your family history and view of Jewish identity?

I think it’s because the wheel of destruction of the Jews was systematic and perfectly organized by the Third Reich. So it means that all the survivors had to have luck — if they lived, it was thanks to the chance, it could not be otherwise.

It plays a role in our Jewish identity, as children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of survivors, because we are all children of luck and chance. We owe our lives to chance. So we owe our lives to luck. It’s necessarily a part of our consciousness. In French, the word “chance” means luck.

So much of the book explores Jewish identity and trauma. How has your Jewish identity changed since writing it? How do you think it will impact what you teach your daughter about Jewish heritage?

Writing this book deeply changed me. If you finish [writing] a book and you are the same person you were before you began to write it, it means that there’s something bad or wrong, because you need to be overwhelmed by the necessity of writing it. So you have to be changed by your book.

Before I wrote the book, I was not comfortable with saying: “I am Jewish.” I never said, “I am Jewish.” Never. People — not people who are very close to people, but people who say they know me — were surprised when they read the book. They said to me, “We didn’t know that you were Jewish.”

Why was I not comfortable to say I was Jewish? For many reasons, but one of these reasons was because I didn’t know what it meant [to have a] secular [Jewish] life. I didn’t know what it really meant to me. Now, after writing this book, I can say, “OK, I am Jewish” and I can describe all the reasons. Now, I try to raise my daughter in a Jewish cultural environment, not in a religious way. For example, we celebrate Yom Kippur, Purim, Pesach and all these celebrations that I didn’t do with my parents.

I don’t know yet how it may impact my daughter. It’s too soon to tell. I have to ask her in 10 years. I am sure she will state that it was not good — that’s normal. That’s the way. We try to give to our children what we missed when we were a child. It’s always the same story.

What has been the most surprising thing about how the book has been received in France?

Success surprises me because success is always a mystery. You don’t know why something is successful. I remember that one month before the launch of the book in France, my mother told me, “Do you really think that our family will interest people? Because we are not sure. People are tired of hearing about us; they are fed up with Holocaust stories. I tell you that because I don’t want you to be sad if nobody buys your book. It’s not because your book is bad. It’s only because people don’t want to hear about that anymore.”

Yes, this success was a surprise. My mother told me that because she wanted to protect me. She knew how hard I worked. But, yes, the second surprising thing is the mail I receive every day. I receive letters, amazing letters, every day, and I try to answer them all.

Do you get postcards?

Often people write postcards or put postcards in an envelope. That’s cute.

Anything else you want readers to know?

I’m so proud to be translated into English. It’s hard for French writers to be translated into English — it’s unusual. It’s so exciting to come to the USA later this year. It’s like a dream for a French writer to travel to the USA and to encounter American intellectuals, journalists and writers. I am so happy.