As a relatively new transplant to New York, and therefore a relatively new transplant into New York Jewish life, I didn’t know how lucky I was to meet Rabbi Avram Mlotek. As I soon found out, he’s one of the most kindest, openhearted, and non-judgmental people out there, and while he identifies as an Orthodox rabbi, his approach to engaging with Judaism is anything but orthodox.

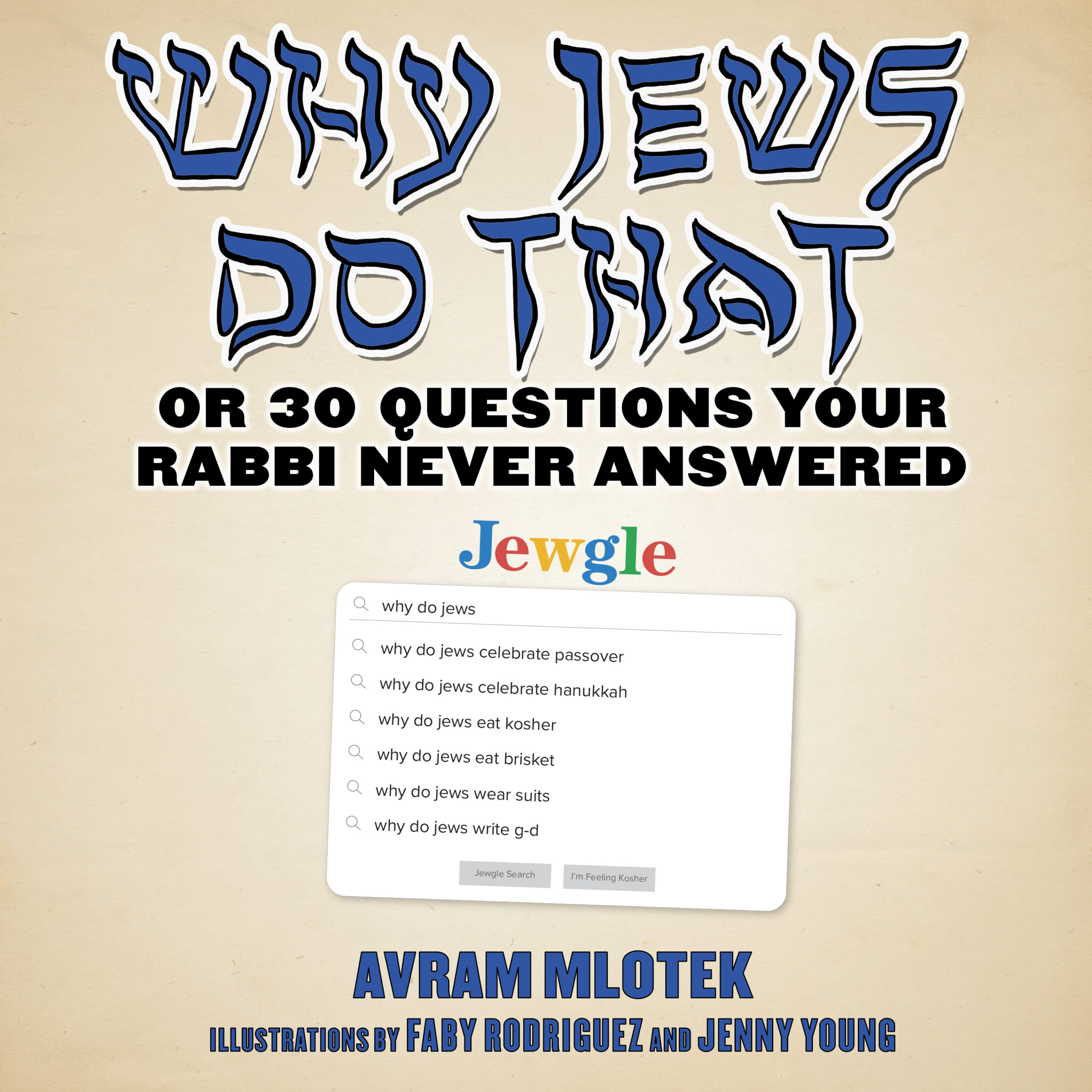

As a co-founder of Base Hillel, he’s welcomed countless young Jews, including myself, into his family home for lively Shabbat dinners, challenging discussions, and volunteer opportunities (of course, only pre-pandemic when it was safe to do so). As a rabbi, he’s made headlines for officiating gay Jewish weddings and challenging traditional stances against interfaith marriages. And now, as a debut author, he’s breaking down and demystifying Judaism with Why Do Jews Do That: Or 30 Questions Your Rabbi Never Answered, which will be released this August. With chapter titles like “I’ve Heard of The Torah; WTF Is the Talmud?” and “Is Pot Kosher?”, the illustrated book offers a fun dive into the many corners of Judaism and Jewish life.

I recently caught up with Avram over email to talk about his inspiration for the book, what it means to be a millennial rabbi, and how Regina Spektor used to change his brother’s diapers.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

As a rabbi working largely with millennials, what are the most frequent questions you hear on a daily basis?

Just the basics, like, “Why be Jewish?” Millennials know Judaism has been around for thousands of years, that their ancestors have died for being called a “Jew.” Yet some of them still struggle to ascertain what this complex, historic heritage has to say to them today and now, especially when they feel increasingly alienated from institutional Jewish life. I think millennials (of which I am one) often get a bad rep from some establishment types insisting they’re “disengaged.” Millennials are just engaging differently and still hungry for learning, community, and connection on their own terms (see: Alma). I think they, we, see a dissonance in what our communities say they stand for and what they practice. Like, how is it that the most traditionally oriented of denominations still supports a president who ruthlessly discriminates against anyone who disagrees with him? That and all the existential stuff, like, “What’s the meaning of life?”

Who do you want to be reading your book, and what do you hope they get out of it?

For starters, anyone reading this article. Also, folks dating or partnered to Jews, and Jews by choice. Ultimately, anyone who ever had a question about Judaism but was too shy to ask. Questions are part of what make Judaism what it is. Could you imagine Passover night without the Four Questions? I hope the book can be a gateway for further Jewish learning and exploration, that it piques your curiosity to Jewgle just a little bit more. That you can feel some pride in your yiddishkeit (Judaism) and be able to laugh at it, too. As the great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem wrote, “Laughter is the best medicine,” and we’re in dire need for a vaccine right now.

What was your favorite chapter/section of the book to write?

By far my favorite part of working on this book was collaborating with students of mine from Base: Jenny Young and Faby Rodriguez, who served as illustrators for the project. Jenny and Faby brought my words to life in ways I couldn’t have anticipated. I wrote this for them, really, and so hearing their enthusiasm, edits, and seeing their creative juices at work was a privilege and joy. One question from the book is, “Why does my Jewish co-worker have so many holidays?” and Jenny made a hilarious cartoon of Oprah giving out holidays to audience members. Faby imagined a boisterous Shabbat dinner with The Dude and cast members from The Big Lebowski in a question dealing with Shabbat. They make the book way funnier, IMHO.

What does it mean to you to be a “millennial rabbi”?

A rabbi is a teacher, a guide, versed in the Jewish Waze. Millennials are at a period of immense transition in their lives, figuring out their professional careers, who they love, where they live, balancing family responsibilities and personal goals. To be a “millennial rabbi” is to be comfortable in that space of uncertainty and doubt that millennials dwell in. It doesn’t mean I need to have “the” answers, but it does mean being rooted in the tradition and capable of responding to people in authentic ways.

When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up? When did you realize you wanted to be a rabbi?

My mom says I wanted to be a writer. My grandfather, Yosl Mlotek, was a Yiddish writer and poet and he and my grandmother, Chana, compiled anthologies of Yiddish songs that served as the basis for much of the klezmer revival’s song repertoire. I was always around music and Yiddish culture as a kid, and as a result, many diverse Jewish communities, like Chabad cheyder camp and klezmer festivals. A high school buddy of mine said to me he always knew I’d be a rabbi (remembering when I co-led Kiddush Klubs on Friday lunches). It was in college, though, when I realized the rabbinate could blend so many of my passions: my love of and belief in Judaism, spirituality, writing, community service, and more. I try every day to make a conscious choice to be a rabbi.

You’ve called yourself an “Unorthodox Orthodox” rabbi. What do you mean by that?

Denominations can be deadly and it’s always a catch-22 of sorts with formal affiliations. For me, my Orthodoxy reflects my commitment to God, justice, humanity, and halakhah [Jewish law], the Jewish pathways of living. I humbly associate my unorthodox Orthodoxy with the unorthodoxies of the Hasidic masters of old, who believed that spirited song and dance could bring you close to God in ways that studying a page of Talmud might not. Thankfully, I’ve found home communities in places like Uri L’Tzedek, an Orthodox social justice group, and other such places.

Last April, you wrote an op-ed for JTA headlined “I’m an Orthodox rabbi who is going to start officiating LGBTQ weddings. Here’s why.” Can you talk a bit about what went into that decision, the kind of backlash you faced, if any, and if you have indeed officiated any LGBTQ weddings since then?

My first day of exams for yeshiva I received a call from a dear friend who had taken a bottle of sleeping pills, wrapped in his tefillin, asking me why God made him the way he did. I stayed on the phone till an ambulance arrived and he is alive, but still a closeted gay man. For me, that morning, almost a decade ago, cemented for me that sexual orientation and acceptance in religious spaces was a matter of life and death. And as I wrote in that piece for JTA, as a Jew, I must choose life. I’ve since officiated a same sex wedding and am consulting and working with other couples now. The decision has sparked fascinating conversations among the liberal Orthodox community with a desire for teshuvot, responsa, around the issue. And yeah, haters gonna hate.

Okay, I know from some top secret intel that Regina Spektor used to be your babysitter. Tell me everything.

Ha! I wish I could tell you I remember Regina playing piano to us in between changing my brother’s diapers but that would very much be fake news. (Though, Elisha, my brother, is a musician himself now, a founding member of Zusha). We grew up in Riverdale [a neighborhood in the Bronx] near Regina’s family. My violin teacher, Sam, was married to Regina’s beloved piano teacher, Sonia. Regina has always been incredibly generous and invited my family backstage at her shows. I think she even recommended Lin Manuel-Miranda come see my dad’s production of Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish. (He did come in the end, though, not with Regina).

Favorite Jewish food?

Let’s be Jewish about this. Generally, I’d say it depends on the season. Boiling hot chicken soup in the summer? That’s basically grounds for exile. That being said, pickled herring is timeless.

All photos courtesy of Avram Mlotek; top image by Jackson Krule.