When the film adaptation of “Tick, Tick… Boom!” was first announced, I was simultaneously elated and terrified. Lin-Manuel Miranda directing Andrew Garfield in an adaptation of one of my all-time favorite musicals? This was too good to be true. This was the stuff of my wildest movie-musical fantasies (and I have many of these). Either I was dreaming or being set up for disappointment.

Turns out I was not dreaming, and I was not disappointed.

“Tick, Tick… Boom!” is a semi-autobiographical piece by writer Jonathan Larson, better known for his Tony-winning and much-beloved “Rent.” It follows Larson in the lead-up to a workshop for what he believes is the musical that will finally give him the success he has been chasing through his 20s. All the while, the people in Larson’s life are moving on, moving out of the city or out of the arts, and he wonders whether he should do the same thing now that he hasn’t “made it” by the eve of his 30th birthday.

The movie itself is a brilliant adaption — and one that is remarkably Jewish in its execution.

For one, the cast is very Jewish. There’s Andrew Garfield (Jewish) as Larson (Jewish), along with a star-studded line up of Jews that includes the likes of Judith Light, Richard Kind, Jonathan Marc Sherman, Danny Burstein, Judy Kuhn and Ben Levi Ross, not to mention a whole array of Very Important Broadway Jews in uncredited cameos. Almost every Jewish or Jewish-coded character in the show is played by a Jewish actor, and they all deliver performances that aim for warmth and realism, rather than cheap stereotypes.

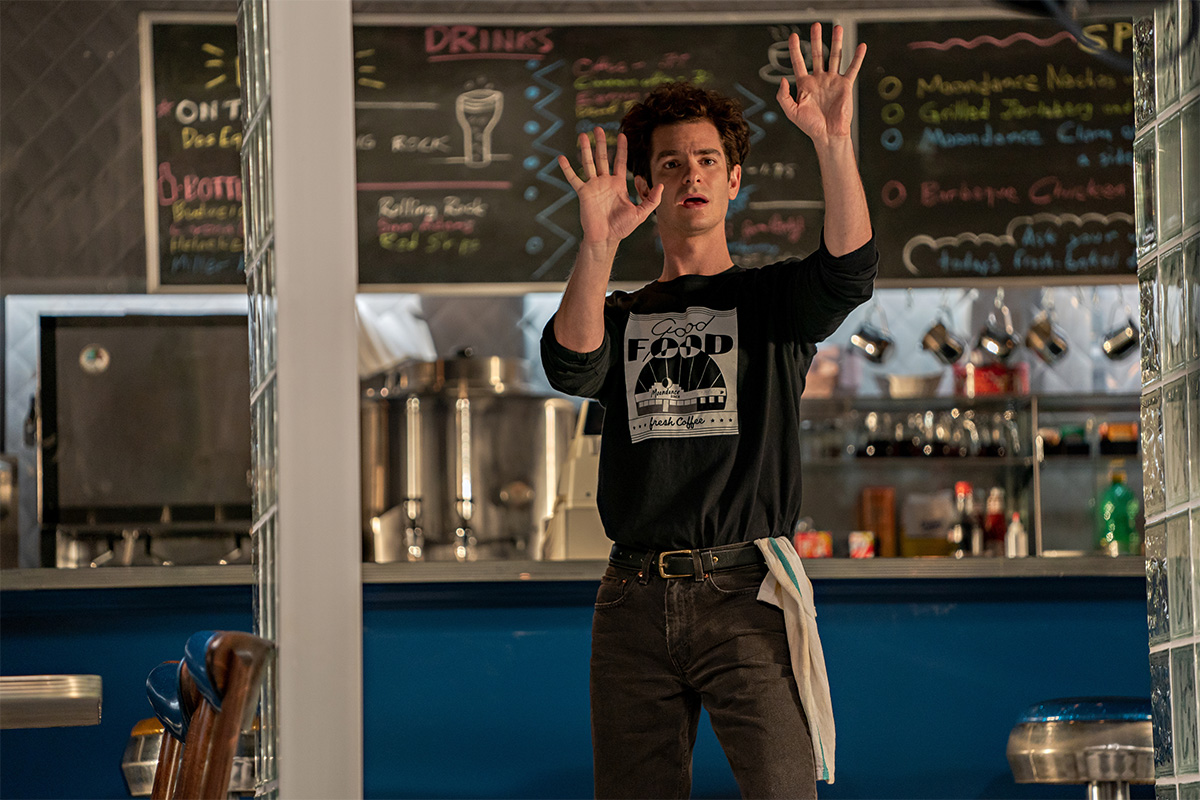

Not only that, but there are explicitly Jewish moments. The first comes in a hilarious scene in the diner where Larson works, where he listens to two patrons try to remember the name of “that Jewish bread.” They eventually land on “holly bread,” and the small, defeated “challah” Larson mutters while taking their order will be very familiar to anyone who has ever been victimized by well-meaning goysplaining. The second comes from a monologue during a key moment of the show, when Larson describes the impact of the AIDS crisis. Larson breaks down talking about watching friends die and speaks of “parents under 50 saying Kaddish for their children.”

Moreover, this all comes in a show that asks again what we’re meant to do as individuals against the relentlessness of human suffering, about the necessity of action anyway, that “actions speak louder than words.” It all feels very Pirkei Avot, a Broadway-ready reminder that “it is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but you are not free to desist from it either.”

I was frankly caught off guard by it all. I came in very familiar with the musical and Larson’s work. While it is not about being Jewish generally speaking, Larson was a Jew who had devoted his life to musical theater and idolized the likes of Stephen Sondheim and other Jewish theater creatives who came before him. Jewishness is an obvious influence in his work. Yet the details of who he was have become largely footnotes to the greater narrative of who he is in relation to “Rent,” and how his death the day off-Broadway previews were set to begin seemed to prove the tagline of the show, that there is “no day but today.” He is an icon in American theater whose death elevated him to a literal legendary status.

And Jews who become legends, the RBGs among us, are almost always universalized, the specifics of their backgrounds, specifically their Jewishness, erased. “Born to parents of Jewish descent,” the Wikipedia page will claim, with the all the additional qualifications that they were self-described as “not religious,” as if that suddenly means they’re not still Jews. The stories that get told of them are made palatable, avoiding the implication that being Jewish mattered at all to who these people were or the work they did. They will be played by non-Jews in the biopics of their lives, and as Jews we’re just supposed to simply be contented that the general public has elevated “one of our own” to the status of sainthood, no matter that we don’t believe in saints.

To the absolute credit of Miranda and Steven Levenson, the award-winning Jewish writer who adapted the script, they deliberately avoided beatifying Larson in bringing this version of him to life on screen. As Miranda explained recently to The New Yorker, they were never “setting out to make ‘St. Jonathan,’ because no one who knew him would argue that he was a saint.” This is precisely why the adaptation succeeds. It never loses sight of Larson,f the person, in the midst of the legend. The portrait of Larson that emerges is one of a gifted creative and at times frustrating friend, who loved the people close to him while being self-involved and ambitious at the expense of most everything else. It’s a very human portrait, and all the more moving for it.

Choosing to cast Jews and preserve Jewish details on screen similarly achieves this sense of authenticity. This film takes the position that in order to render the most authentic portrait of Larson possible, all the details matter. The specifics of his identity and the people he was surrounded by matter as much as the sets and costumes. Miranda, who has not shied away from allowing his life and identity to inform his work and public persona, recognizes that Larson was not transcending his background to write something with wide appeal. Rather, that context is where the work emerges from, and is therefore essential to the story.

Ultimately, Miranda’s “Tick, Tick… Boom!” is a fitting tribute to a writer who has meant so much to so many. It is a firm rebuke to the idea that Larson’s death somehow matters more to his legacy than the life he lived, and one that’s staying with me for a long time.