College has been a time of challenging my identity in new and sometimes uncomfortable directions. This applies to all aspects of my life, but especially to my Judaism. For me, there will always be running list of questions: “How Jewish am I?”; “What does this ritual mean for me?”; “How much do I adapt my practices to meet the values of modern day society, versus what traditions and social values do I stand up for and staunchly defend?” I may place Judaism as an intrinsic aspect of my identity, but what this Judaism looks like is malleable, and it must adjust over time to match the values of the world in which we live.

Which brings me to smoked meat.

Nowadays, with increasing awareness of animal rights and the escalating climate crisis, the classic, mountain-high sandwiches of my childhood don’t quite sit right with me anymore. The thought of consuming piles and piles of red meat in a checkered, Jewish-American deli no longer strikes me as mouth-watering so much as antithetical to my values.

I am a committed vegetarian, and I have been since first-year since I read a frightening New York Times headline that spelled climate change doomsday on the horizon. Cutting down on meat consumption while in college felt like one of the only actions I could take on an individual level to combat this mounting crisis. So, when tradition clashes with personal politics, it’s l’dor v’dor versus tikkun olam, leaving me caught in a proverbial pickle.

Smoked meat is a Montreal food icon, and there is an inspiring history behind the brisket. Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants arrived in Montreal in the late 1880s with the recipes of the Old World tucked into their back pockets. These early restauranters perfected the method for Montreal-style smoked meat by salting, then curing, slices of beef. Then, they would season the smoked meat with a careful blend of mustard seed, garlic powder, coriander and garlic. As Jews settled around the lower Plateau and Westmount, they erected businesses to serve and sell their precious family recipes.

Yet, as a young person today, I needed to think critically about whether I could stomach a dish that author Mordecai Richler called “the nectar of Judea,” or if I could engineer an equally Jewish meatless alternative. Without wasting any more time, I decided to put my mustard where my mouth was. Using our favorite meat alternatives, my roommate and I set out to determine whether we could recreate the taste of that beloved smoked meat sandwich minus … you know … the meat. Here’s how we fared.

The Bologna Tofurkey Sandwich

This seemed simple enough. A de facto version of the original dish, replaces the beef with a chemically induced, Margaret Atwoodian meat alternative. Everything else remained the same: toasted whole wheat rye bread, coriander, sugar, and onion powder for some seasoning. As a side dish, we also purchased a small container of pickles from a local European grocery store. For the dressing, we kept it simple: Schwartz’s Deli brand yellow mustard. You cannot go wrong with a classic.

It tasted like how I expected. The simulated bologna was saltier than the real thing, but not so artificial that you had to plug your nose and hope you could not taste it. The pickle was also a perfect accoutrement, and not just for the aesthetics. Our only hesitance had more to do with what we were ingesting, not so much the taste of it. The list of ingredients for the Tofurky contained some words I could not pronounce, as well as some other ingredients that just felt completely alien to me. For example, what was seaweed and beetroot powder doing in my lunch?

Overall, the smoked Tofurky sandwich was a decent alternative to the meat sandwiches I knew and loved. It will never replace the real thing, and I still cannot help but wonder whether I ate something that was engineered in one of Victor Frankenstein’s labs, but it was nevertheless a lovely vegetarian bite.

You Don’t Know Jackfruit

Jackfruit sounds like one of those foods you can exclusively find in the top level of a yoga mom’s pantry. A fruit originating from southeast Asia, jackfruit is loaded with vital nutrients like protein and Vitamin C, making it a common substitute for meat in vegetarian and vegan cooking. Could a foreign fruit be flavorful enough to recreate the kind of sandwich that our Jewish ancestors perfected when they immigrated overseas?

We tore the jackfruit apart with our hands to make a smooth, pulled texture, reminiscent of those lean slices of brisket that fall apart into bits and pieces at a kosher deli in Montreal. Then, we sauteed the jackfruit in a pan with slices of white onion, mustard seed, and our own homemade barbecue sauce for about an hour. For this sandwich, we aimed to preserve texture over moisture, so it did not matter to us too deeply if our meat was swimming knee-deep in sauce.

The result was a sandwich that recreated the delicate mouthfeel of brisket but was far too saucy to match the kind of traditional smoked meat that is dried in a methodical manner for weeks at a time. In the end, jackfruit proved to be more than just some exotic, healthy food trend, but a legitimately delicious – and protein-packed – meat alternative.

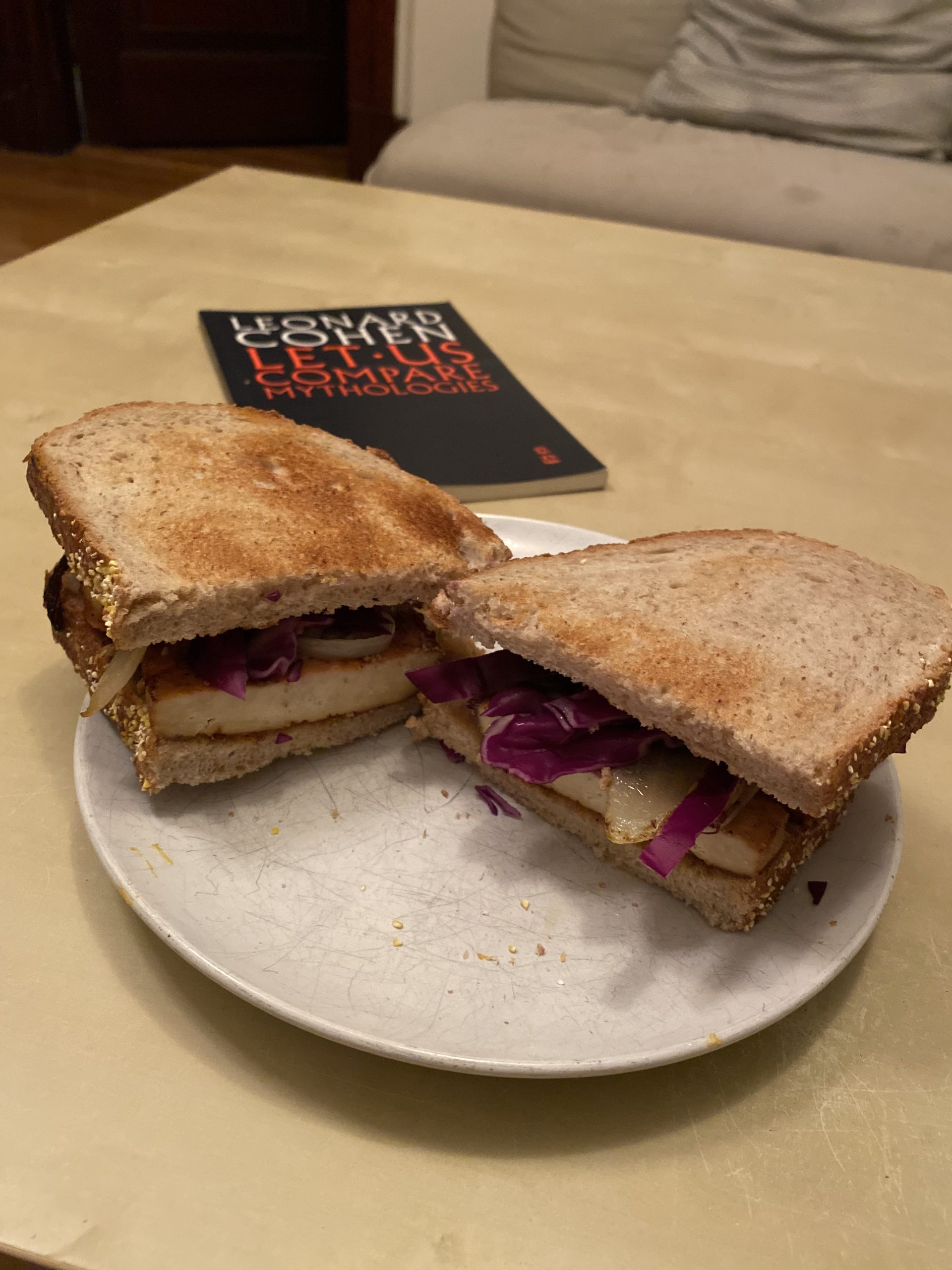

The Tofu in the Rye

Our last experimentation of the evening was also our simplest. For about thirty minutes, we marinated a package of firm tofu in a bowl of barbeque sauce, honey, vinegar, and salt. Then, we added steak spice on top of the dish to give the tofu some classic, smoked meat flavor. Fun fact: Most store-bought steak spice is technically vegetarian. Maimonides is kvelling!

Instead of serving the tofu plain on rye bread à la classic American delis, we added caramelized onions and slices of red cabbage to give it more of a robust, juicy sandwich taste. Then, of course, we served the sandwich with a pickle on the side.

While the tofu was dry enough to compare to smoked meat, the tofu was far too firm to even compare to brisket. However, the caramelized onions were a nice touch, even if it was a slight departure from Jewish tradition.

In the end, we were both sourly disappointed, but maybe we had set ourselves up to fail. We yearned for what we knew and remembered, and what we knew was rye, deli mustard and slices of spiced, brined beef brisket. Besides, neither of us could rewrite a tailor-made, century-old process in a single afternoon.

Thus, when I eventually returned to my preferred Montreal smoked meat restaurant the next day, I could not help but breathe a sigh of relief. When I took a few bites from my friend’s plate — a move which officially broke my two-year streak of vegetarianism — I could not help but feel like I was breaking some unwritten rule of kashrut. In returning to my beloved Jewish traditions, I was, in a way, breaking another form of dietary laws I had set for myself.

But I know that the occasional indulgence in a childhood classic does not make me a “bad progressive” or a climate change denier. Like a lot of politics, vegetarianism is not a maximalist game of all or nothing. I do not have to forgo my Jewish traditions entirely and live a monastic, vegan lifestyle, nor do I have to acquiesce and become a carnivorous, deli-dwelling dinosaur. Respect for tradition and concern for the planet’s future can coexist on the same plate. It’s time to embrace some delicious middle ground.

So leave the tofu for the stir-fries and pass me some steak and beef seasoning. I’ll have what she’s having! (Just only every now and then.)