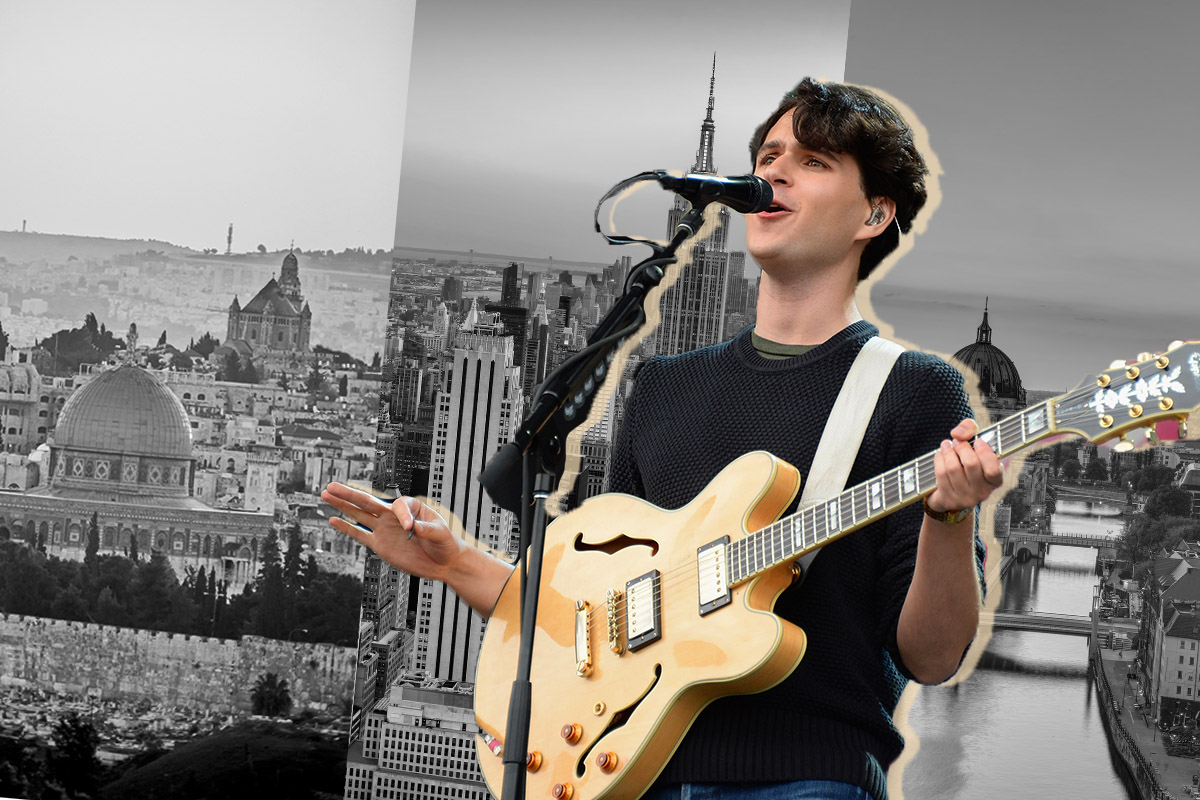

I used to roll my eyes when someone said they felt seen by a song. It sounded so dramatic — and that’s coming from someone who listens to Mitski while staring at the rain from a train window. But “Jerusalem, New York, Berlin,” the last of 18 tracks on Vampire Weekend’s highly anticipated new album Father of the Bride, sees me on so many levels.

I know. I cringed, too, but stick with me.

The song initially appealed because, when listed together, the three cities conjure an immediate Jewish connection (why are Jewish references in popular culture so thrilling?!). Jerusalem is a no-brainer; New York is home to the largest Jewish population outside Israel; and Berlin was the epicenter of the Holocaust.

There was also an immediate personal connection. Jerusalem represents my past — I spent a year in seminary there at 18, and made aliyah (emigrated to Israel) after college; New York is my present — my home for the last 18 months; and Berlin is my future — an affordable cultural hub that’s much closer to my UK-based family where I plan to live next.

When I hit play, the Jewish connection developed. “A hundred years or more,” crooned band front man Ezra Koenig, alluding to the Balfour Declaration, a public statement issued by the British government in support for the creation of a Jewish state. “It feels like such a dream/An endless conversation since 1917.” Israel has certainly been the topic of endless conversation since I can remember — from heated political discussions at Shabbat lunches to chanting “We believe in the torah/We believe in avodah [work]/We believe in aliyah” at Jewish summer camp, to clashes with anti-Zionists on my college campus to marches protesting Netanyahu’s government in Tel Aviv. These conversations were so all-encompassing that after hiding in bomb shelters and refreshing Ynet’s live news updates incessantly during Operation Protective Edge, I resolved to limit my Israel news intake — for the sake of my mental health.

A couple of verses later, Koenig addresses the perpetrators of modern anti-Semitism and collective trauma of the Holocaust, singing, “Don’t let them restart/That genocidal feeling/That beats in every heart.” My own heart sank as I remembered the Kantor Centre’s 2018 report, which states a 13% increase in “major violent” anti-Semitic incidents worldwide.

This is no rogue “l’chaim” in a Black Eyed Peas hit; Vampire Weekend has dug deep.

I wanted to know more about Koenig’s inspiration — no easy task given his notorious allusiveness. After an excessive amount of Googling, I found an interview with Coup de Main magazine where he explained that the song asks the questions, “What does it mean when you identify with something bigger than yourself? As big as an ethnic group? Or religion?”

Okay, now the levels of seen-ness were bordering on creepy: These questions have lingered in my mind ever since I singled myself out as “different” by leaving my Christian high school early on Fridays to get home before Shabbat. No matter where I reside, Judaism has always been an integral part of my identity. In Jerusalem, it battled with itself as I struggled to fit into the one-size-fits all yeshiva scene — yes, I’d studied the entire Tanakh in Hebrew, but I also wore a bikini at the beach. Riddle me that, rabbi! In New York, it propelled me to the Lower East Side, with its tenement synagogue and Yiddish-speaking butcher who kvelled over my love for chopped liver.

But when it comes to Judaism and Berlin, things start to get murky. Plans to move have already provoked a strong reaction from my grandmother, who assures me she will never visit that place. It is too entwined with the Holocaust, too painful to comprehend moving past. I feel guilty that I don’t feel the same.

While the thought of passing the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe — and the horror the name alone arouses — as I go about my daily business in Berlin is uncomfortable, the concept of regularly confronting the Holocaust is familiar. It has always loomed over my life, an inherited, collective trauma that caused my third-generation British parents to consider leaving their home as anti-Semitism rose in their beloved Labour party, that discernibly fuels the stubborn sentimentalism of every sabra I met in Israel.

The Holocaust has shaped my identity, but my lack of first-hand experience with it allows me the distance to move past it, albeit warily. And I’m not alone. Hordes of Israelis — somewhere in the range of 10,000-15,000 — have relocated there in search of a cheaper, more peaceful alternative to Tel Aviv. They’ve created a contemporary Jewish life that’s culturally much more Israeli that it is Ashkenazi/European, opening Hebrew-speaking kindergartens, a Hanukkah market, and eateries serving traditional mizrahi dishes.

To me, “Jerusalem, New York, Berlin” is a song about yearning for hope. The lines, “All I do is lose baby/All I want’s to win,” are repeated with each chorus. Berlin’s burgeoning Jewish future — with its artists and technology, tradition and innovation, diversity and community — is hopeful. I can’t help but be drawn to it, like a moth to a flame.

Header Image: of Ezra by Theo Wargo/Getty Images, of Jerusalem by John Theodor/iStock/Getty Images Plus, of New York by lucky-photographer/iStock/Getty Images Plus, and of Berlin by elxeneize/iStock/Getty Images Plus