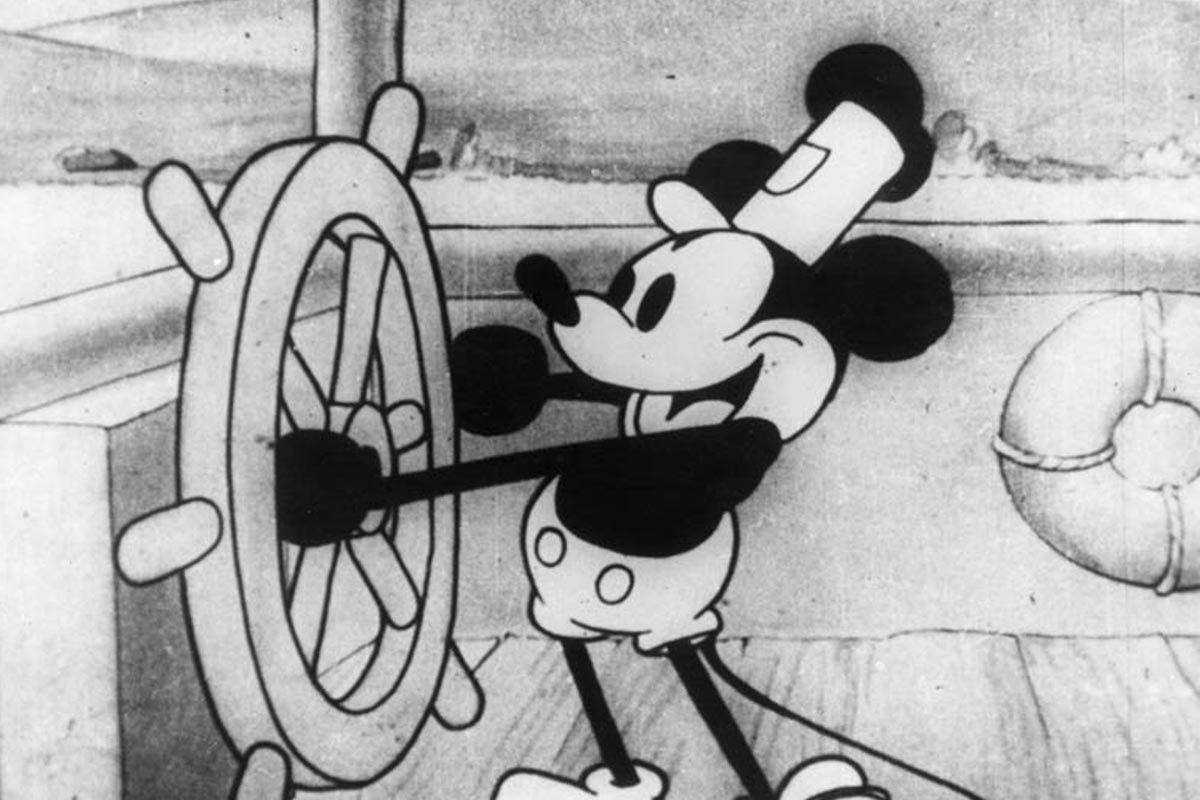

Was Mickey Mouse supposed to be an anti-Semitic caricature of Jews? Great question! In the series finale of Broad City, Ilana tells Abbi, “Walt Disney was like, um, jizzing basically for rich Euros and feudal lords, and Mickey Mouse was supposed to represent a dirty little Jew, straight up.”

Is this true? We had to investigate.

Let’s begin with the claim that Walt Disney was anti-Semitic. Even Meryl Streep thinks so; she once called Disney a “hideous anti-Semite” who “formed and supported an anti-Semitic industry lobby.”

Disney’s biographer Neal Gabler somewhat disagrees, writing, “Though Walt himself, in my estimation, was not anti-Semitic, nevertheless, he willingly allied himself with people who were anti-Semitic, and that reputation stuck. He was never really able to expunge it throughout his life.” Basically, he’s saying he may have not been anti-Semitic himself, but he did not make any effort to distance himself from anti-Semites.

So where does Ilana come up with the idea that Mickey Mouse was created as an anti-Semitic caricature of Jews?

Maybe she was on Twitter; there’s a tweet from 2009 calling Mickey a “crazy Jewish rat” and there’s another one from 2011 that reads “fuck off mickey you racist, anti-Semitic little rodent.”

There’s also this tweet, which is arguably way more fun:

[to the tune of "This Is How We Do It"]

Mickey Mouse is Jewish

— Zach Dunn (@zachbdunn) June 12, 2018

But, more likely, she could have come across this idea in a famous graphic memoir. Let’s turn to Art Spiegleman’s Maus. Bear with us.

Spiegleman, an American cartoonist, wrote and illustrated Maus. Initially published in increments in Raw, a comic anthology, it is best known as a graphic novel that was first published in 1996. It won a Pulitzer Prize. The story is of Spiegleman interviewing his father, a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor. In the depictions, Jews are mice, Germans are cats, and Poles are pigs. Maus was narrated to a mouse named “Mickey.”

Where did Spiegleman get the idea to depict Jews as mice?

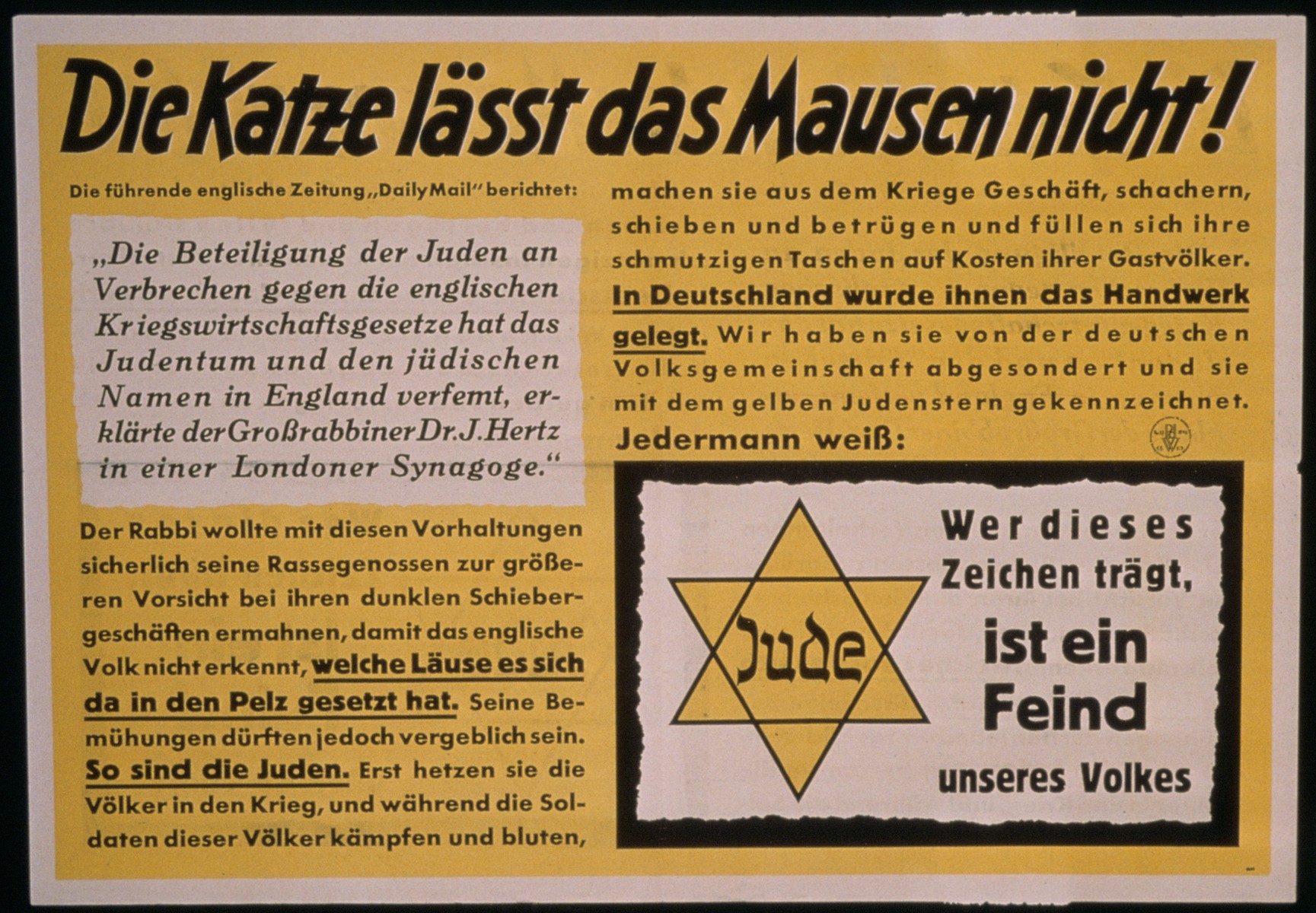

Nazi propaganda that depicted Jews as vermin. In the anti-Semitic propaganda film The Eternal Jew, the narrator explains, “Just as the rat is the lowest of animals, the Jew is the lowest of human beings.”

Spiegleman cites The Eternal Jew specifically, explaining in the New York Review of Books that it was “the most shockingly relevant anti-Semitic work.” He explained the film “portrayed Jews in a ghetto swarming in tight quarters, bearded caftaned creatures, and then a cut to Jews as mice — or rather rats — swarming in a sewer, with a title card that said ‘Jews are the rats’ or the ‘vermin of mankind.’ This made it clear to me that this dehumanization was at the very heart of the killing project.”

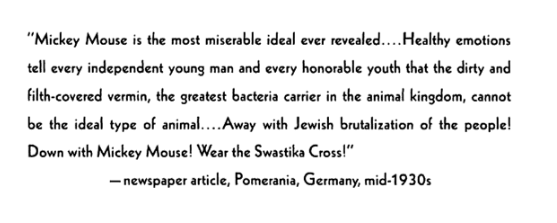

Let us now direct your attention to the epigraph of Maus II:

If you can’t read the image, here’s the text, which is quoted from a German newspaper article from the mid-1930s: “Mickey Mouse is the most miserable idea ever revealed….Healthy emotions tell every independent young man and every honorable youth that the dirty and filth-covered vermin, the greatest bacteria carrier in the animal kingdom, cannot be the ideal type of animal….Away with Jewish brutalization of the people! Down with Mickey Mouse! Wear the Swastika Cross!”

Nazi propaganda directly connected Mickey Mouse to Jews; Spiegleman is simply picking up on this trope and subverting it.

As scholar Linda Hutcheon writes, “In drawing Jews as mice, then, Spiegelman counter-discursively answers back to this cultural association, reappropriating and resignifying a negative image that once fueled anti-Semitism, in part by showing precisely how such ‘mice’ were made into the victims of sadistic Nazi ‘cats.'” Hutcheon argues that the epigraph centered on Mickey Mouse “points to important historical connections not only between mice and Jews in the Nazi imagination but between Maus and the history of the mass culture form of the comic genre.”

Anyhoo, all this is to say, linking Jews to Mickey Mouse may not have been Disney’s original intent, but it became a thing in the Nazi imagination.

“The Barnyard Battle,” a 1929 Mickey Mouse cartoon, was banned in Nazi Germany. In it, Mickey and his mouse pals defend their farm against German cats. As the New York Times reports, “The German censor banned ‘The Barnyard Battle’ on the grounds that ‘the wearing of German military helmets by an army of cats which oppose a militia of mice is offensive to national dignity.'”

Again, nothing Jewish here, just pointing out that the German-as-cats metaphor existed long before Maus.

Here’s another piece of Nazi propaganda, from 1942. In German, the title reads, “The cats will not let the mice be!” (Nazis = cats; Jews = mice.)

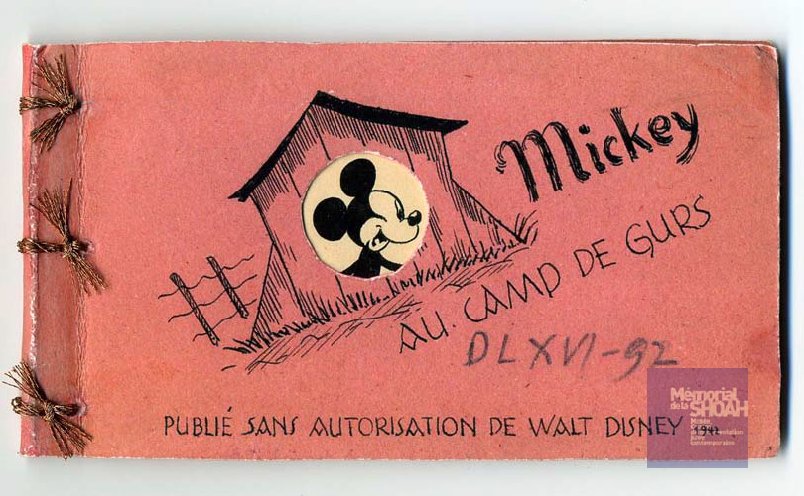

In MetaMaus, Spieglelman’s look inside Maus, he writes, “Years after Maus, I discovered there was a cartoon booklet drawn in 1942 by a prisoner in a French internment camp (he died in Auschwitz later that year), called Mickey in Gurs — another validation that I’d stumbled onto a way of telling that had deep roots.”

(Here’s a thread about the comic you should read!)

We could keep going…

All this is to say: There’s really no way to know whether or not Walt Disney intended Mickey Mouse as an anti-Semitic stereotype. We don’t know whether or not he thought of Jews as mice/rats/vermin. But what we do know is that this trope was echoed in Nazi propaganda, with one newspaper (and most likely many others) equating Jews with Mickey Mouse himself. And, decades later, Art Spiegleman consciously depicted Jews as mice, as a way of subverting Nazi propaganda in telling a Holocaust story.

So when Ilana says in Broad City, “Mickey Mouse was supposed to represent a dirty little Jew, straight up,” it’s not necessarily true — but also not necessarily false.