My cousin Stephanie and I have always had a lot in common. We were born in the same year, raised just a few suburbs apart from one another. We both took up figure skating at the ripe old age of 3. Throughout our childhoods we could be seen sporting the same jean jackets and side ponytails (miss you, ‘90s). And after high school, even though we set off for different colleges and paths, we remained close and connected in a way that only cousins can.

But in the last six years, Stephanie’s life has changed in a way that I can barely comprehend, let alone relate to. In October of 2013, her mother, Susan — also known as Aunt Suzy, my mother’s sister — suffered a cervical aneurysm. After that, things felt a little “off.” She’d be at her local nail salon, the same one that she’d been going to weekly for years, and suddenly not know where she was. After continuing to demonstrate memory problems and other cognitive issues, she was eventually referred to a neurologist. Just prior to her 60th birthday, in the spring of 2016, Susan was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer disease.

According to the Alzheimer Association, about 5% of the more than 5 million Americans with Alzheimer disease have the younger/early onset form, which is specified as affecting people 65 and under. It’s difficult to diagnose, as doctors aren’t typically looking for signs of dementia in younger patients. But it also tends to advance quickly, something Stephanie can attest to after witnessing her mother turn into a completely different person over the past several years.

These days, Stephanie, 33, lives with her parents and works part-time, about 30 hours, at a university bookstore in Chicago. Most other hours are spent taking care of her mom, a job she shares with her dad (she has one younger brother who lives out of state). Over the past few years, I don’t know if I’ve gotten through a single phone call with Stephanie without crying — over hearing the suffering of my aunt, but also the suffering of my cousin, who never expected to be taking care of an ill parent in her early 30s.

I wanted to hear more from Stephanie about this experience and give her a platform to connect with others who may be going through something similar. So, from our different worlds, we recently chatted over the phone to talk about life these days.

When you first learned of your mom’s diagnosis, what was your immediate reaction?

I had no idea what it was. I had to do my research. We had seen the signs before the official diagnosis — stuff wasn’t the same. I guess there was a little relief in getting a name to it, but then it was like, okay, what do we do? How long do we have? What’s going to happen? What next?

Can you walk me through a typical day for you right now?

Dad gets her up in the morning. We get her to go to the bathroom. Then we help her pick out clothes and get her dressed for the day. She goes and takes her meds and eats breakfast. On Mondays through Fridays, around 8:30 a.m., she gets picked up by a transport van to go to an adult day care program run by the Council for Jewish Elderly of Chicago. We’re told she does activities there like art and music. She gets home around 4-ish and we give her a snack. We watch some TV and have dinner. Then around 7:30/8 p.m. she’s taking her meds and getting ready to go to bed.

When I hear you describe that day, I can’t help but think it sounds exactly like if you were taking care of a child.

Yes, exactly.

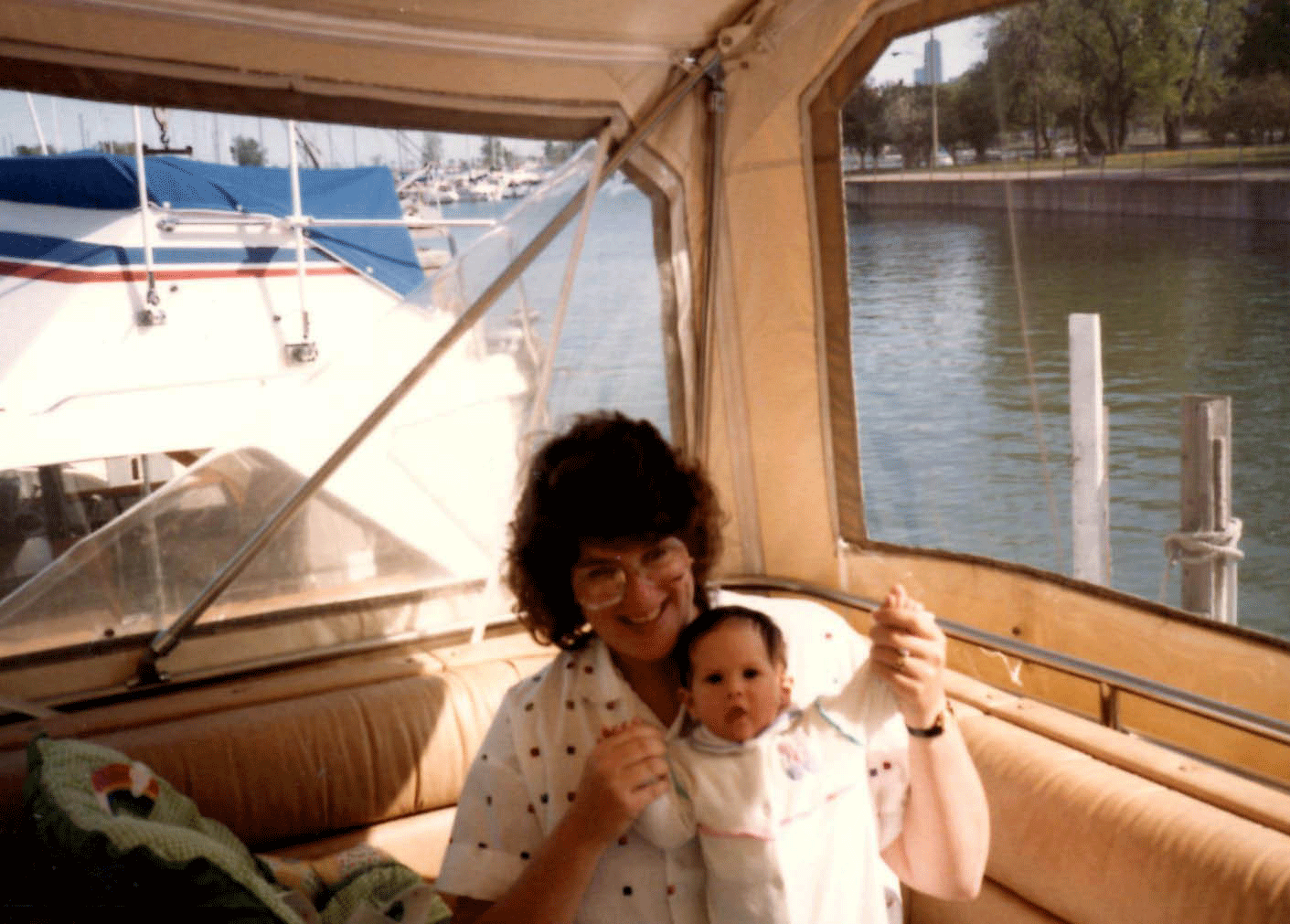

Stephanie and her mom, 1986.

Stephanie and her mom, 1986.

What’s that like for you?

Think about when you babysat for young kids, when they were like 3 or 4 and learning things like walking and going to the bathroom and how to be more independent. Now dealing with Mom is like dealing with a young child, except where the child learns and gets more and more independent, Mom is forgetting everything that she knew, and each time she goes to do something, whether it is using the toilet or showering or eating at the table, we have to reteach her how.

It’s hard. It’s harder than I ever thought it would be. Trying to take care of a parent who’s looking back at you like you shouldn’t be taking care of me, I should be taking care of you — it’s a hard thing to look at every day.

What does the disease actually look like? What are the symptoms?

As things have progressed, Mom sleeps more and more or just lays in bed. She has lost her ability to use a telephone or even the TV remote. She will listen to music and occasionally sing along with what is playing, but she rarely speaks and when she does, it is only a few words at a time. Most of the time it is random words that don’t seem to be connected to what’s going on.

She forgets where she is, where we are, what time it is or even the season. There is a disconnect between her thoughts and what comes out of her mouth. She no longer knows the who, what, when. But there are times she can remember in detail things from her childhood. She’s remembering other times, and not what’s in the present. She’s confusing then with now, that’s the best way I can put it.

I think people hear Alzheimer disease and think, oh, they forget things, but it’s so much more than that.

It’s not even they forget things — they forget how to go to the bathroom, how to shower. Doing everyday activities becomes a lot harder. Eating, the idea of holding a fork — you have to relearn everything you learned as a child.

And unfortunately, it is a disease with no real cure. It progresses in each person differently, but statistics show that someone with a diagnosis of early onset Alzheimer disease has an average survival of 5-7 years starting from when first symptoms appear. So more than forgetting things, it’s watching the person you have known your whole life disappear before your eyes while also knowing there is nothing you can do to stop it.

I know there are times when she doesn’t remember who you are. What is that like?

I think I’ve accepted it. There’s nothing you can do. Coming back from a four-day vacation recently — it was a disaster. She started pushing me away, didn’t realize who I was, that I’m her daughter. She just kept looking at me like, “Who are you?”

High school graduation, 2004.

High school graduation, 2004.

What kind of support are you getting?

I have a support group the first Tuesday of every month out in the suburbs for kids around our age who have parents with a disease. It’s hard — we’re all at different stages. I’ve now watched two people in my group lose a parent. But it’s good support because they understand what I’m going through. It’s given me ideas of what I can do, things I can try.

Have you been able to talk about this with friends?

My best friend from college, her mom also has the disease but she’s in an earlier stage, so we talk a lot. And I have one close friend who lives here who I talk to all the time — she lost her dad. They’re my main support system.

Does anyone ever say insensitive things to you about it?

Every once in a while friends can be like, you just need to get over whatever you’re dealing with. It could be worse. But to me, what can be worse than this?

What do you think is the most helpful thing that friends could do for you right now?

Just be there. Give the support. Know that I need it now, but I’ll need it later, too. Don’t just check in one time — continue to be there throughout the whole thing.

Do you feel like, during this time, you’ve had to put your own life on hold?

Yes. I only make plans with friends who will understand if I have to cancel them. Not everybody’s understanding of what’s going on. I have definitely learned that.

What about dating?

Oh, I haven’t done that in a while.

Because of this? Not having the time or energy?

Yes. Trying to explain to every person that this is what’s going on in my life, welcome to… whatever. I don’t want to put the pressure on someone. At this point if I meet someone, it happens, but I’m not going to go out of my way to start dating.

Are you angry about that?

I have my moments. Sometimes it’s like I want to live my life, too. I want to go away. I want to do things. But then sometimes you have regrets if you do live your life, you feel that guilt. Everyone keeps saying you need to live your life, you need to do stuff for you, too, not just take care of your mom. But it’s hard.

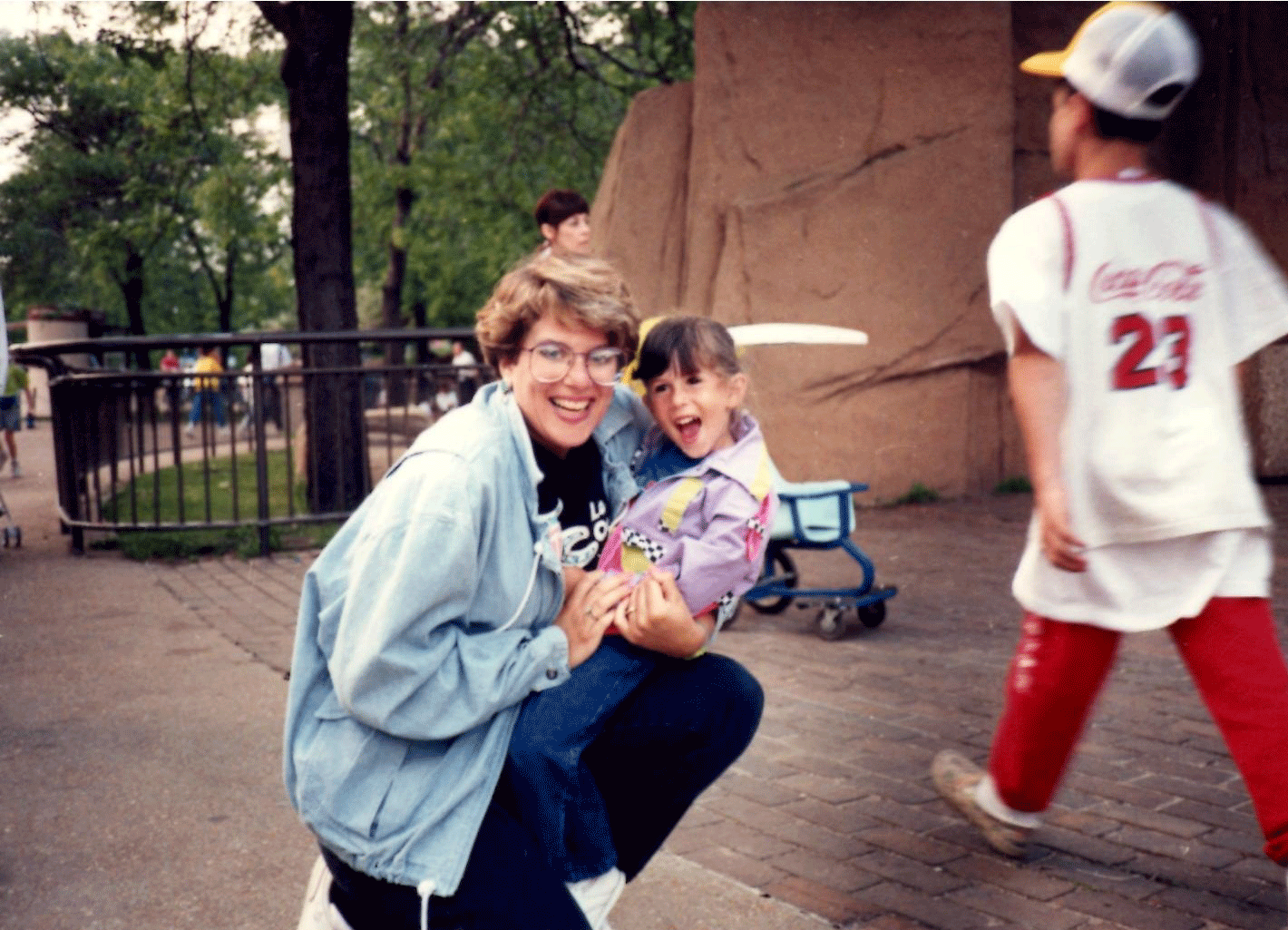

At the zoo, circa 1991

At the zoo, circa 1991

Do you have any self-care practices?

I get my nails done every other week. That’s “me time.” And I go the gym twice a week, where I can detach from my cell phone.

What is it about detaching from your phone?

No one can bother me. But then there’s also the backlash: What if something happened and I didn’t have my phone near me? I won’t know if there’s an emergency.

Okay, I don’t know how to word this. I mean… okay, I’m going to be blunt, we’ve talked about this. You know that your mom probably doesn’t have that much longer to live. How… what…

How do I feel about that?

Yes, how do you feel about that?

This will sound horrible, but I’m ready. I need to move on with my life. I want to take her out of her pain and misery. And I think there’s a lot of stuff that I haven’t grieved over, that I need to have closure on as well. And I won’t have that closure until I have closure on this. A lot of emotions have been in my head for the past six years. It’s time.

Are there moments when your mom still feels like your mom?

When she sings. Her eyes light up when she hears songs she remembers, like anything by The Beatles. And she still loves going to temple every Friday night.

Thank you for talking to me about this.

Thank you. This is something neither of us ever expected to be doing.

This interview has been edited and condensed. All photos courtesy of Stephanie Levine.