I distinctly remember the day before Yom Kippur of 2011, when I explained to my sixth grade teacher that I would not be in school the next day. He laughed.

“You Jews have so many holidays, all you do is have fun! Why can’t I be Jewish?”

Little did he know, right? I remember wanting to explain to him that while Yom Kippur is a holy day, it does not fit the traditional definition of a “holiday,” but I couldn’t find the words. Besides, I knew he wouldn’t really understand even if I managed to.

Looking back on this interaction now, I can feel the lingering frustrations of my 12-year-old self. With time, though, my bitterness has been muted thanks to a crucial realization: Yom Kippur is just another classic case of what I like to call Jewish Cynicism. Though it may not always be explicitly labeled as such, Jewish Cynicism is an undeniable knack for unearthing darkness, often to prod sarcastic humor out of tragedy. It’s the kind of shockingly blunt commentary your bubbe might provide at the dinner table. And it can be found not only in our holidays, but in pop culture, our humor, and of course, our books.

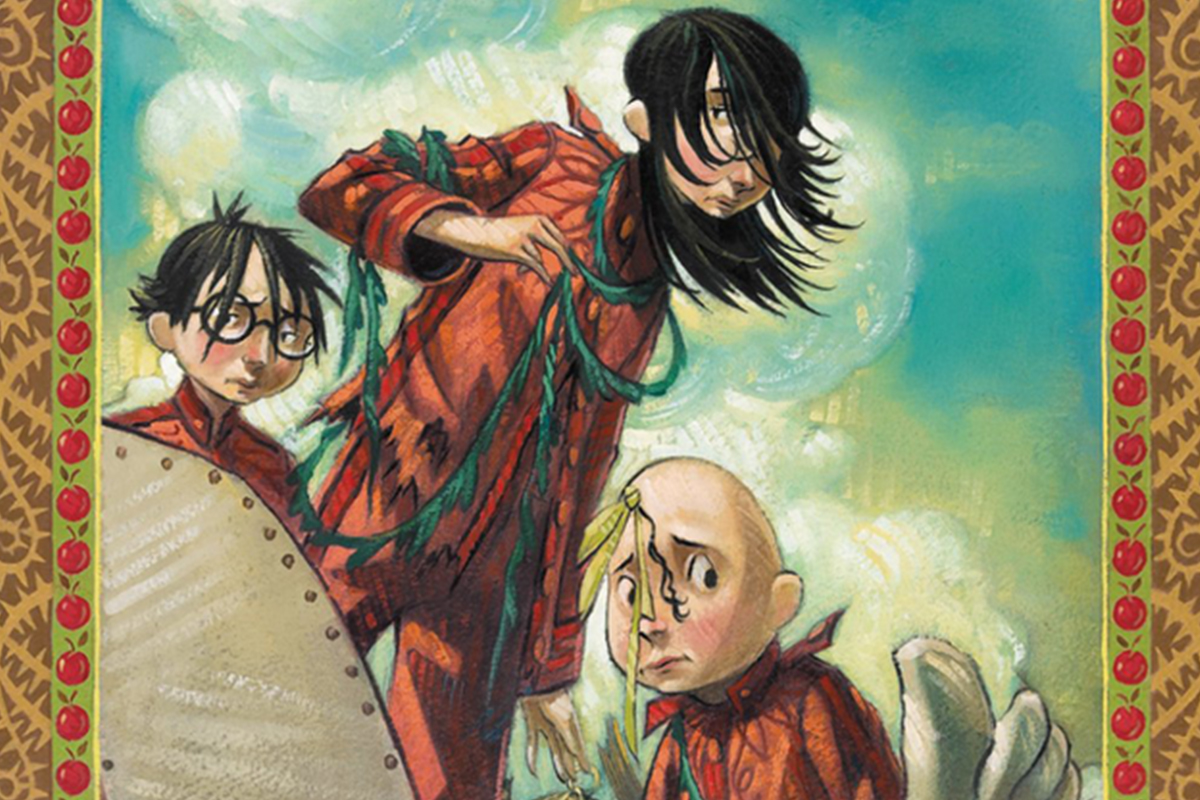

Let me give an example. The first time I stumbled upon Jewish Cynicism, it was wrapped up in Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events. To those who may not be familiar, the children’s series by Snicket (the pen name of Jewish author Daniel Handler) details the misfortunes of the orphaned Baudelaire siblings: Sunny, Klaus, and Violet. Throughout the series, the brilliant trio are cared for by a rotating cast of incompetent guardians while Count Olaf chases after their family fortune.

Even to the untrained eye, these children’s books are a rare delight. But if the reader approaches Snicket’s work from a cynically Jewish lens, that’s where the real thrill lies. To me, at least, there’s something deeply Jewish in the unfairness with which the world treats the Baudelaires. Though they are witty, loveable, and fiercely protective of each other, hardly anything ever goes their way. Ring any bells?

As a child reading the series, I didn’t know that Handler is Jewish, but I recognized in his writing something I knew Jews had encountered plenty of: injustice. The unfairness of Snicket’s work is palpable, as no one is more deserving or deprived of a happy ending than the Baudelaires. The siblings’ predicament is so devoid of joy it becomes comedic, almost a mockery of devastation itself.

A catastrophe that is, unfortunately, not fictional can be found in the 2018 accusations against Handler alleging sexual misconduct. It was disturbing to learn this fact about a favorite childhood author of mine, as these accusations create true darkness where before it was merely suggestive. Thankfully, the Baudelaires’ escapades are not the only examples of Jewish pessimism in literature…in fact, far from it.

The more books I have read by Jewish authors, the more I’ve grown to understand something significant about Jewish people: We love sadness. Or rather, after being exposed to it so many times, Jewish writers are capable of manipulating sorrow to evoke laughter, tears, or any other expression. Nathan Englander’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank is a beautiful example of this phenomenon. In this work can be found 10 breathtaking stories, each one grappling with a different component of what it means to be Jewish. The opening story (which shares the book’s title) wraps up with two super stoned middle-aged couples standing in a pantry. It sounds humorous enough, but this changes when the couples decide to play what is potentially the most twisted game I’ve ever heard of: One person is assigned the role of Gentile, while the other is the Jew. Next, the Gentile decides, if ever there were to be a second Holocaust, if they would hide and protect the Jew.

Heavy stuff, I know.

I’ve spoiled enough of the story, so I won’t go on about how it ends. What I will touch upon is the shock I felt reading about the Righteous Gentile game, and what it reveals about Jews. Our cynicism can enable us to vividly theorize our traumas, and in some ways, even relive them. After learning there are Jewish people who are actually willing play this game, it’s been made clear to me that revisiting pain is integral to modern Jewish identities. And how could it not be? After all the suffering Jews have endured, modern day Jewish people cannot be completely separated from a historical and ongoing legacy of hurt. After I found myself personally toying with the idea of the Righteous Gentile game, I know I certainly can’t.

On one of my recent Google deep-dives into the world of Jewish pessimism, I stumbled upon the Hebrew term middah k’neged middah, which translates to “measure for measure.” Similarly to karma, middah k’neged middah proselytizes that those who do good will receive commensurate good unto them, and vice versa for those who do bad. Though I like the sound of this concept, I struggled when asking myself how I should relate to it. Granted, the Jewish people have not always been benefactors of middah k’neged middah. Whether it be found in depressing children’s literature or Jewish adult fiction, the answer to this conundrum lies in Jewish Cynicism.

After all, Jewish Cynicism enables its users not only to confront trauma, but to grapple with it — whether by humor, candor, or any other mechanism for coming to terms with heartbreak. It is thanks to Jewish Cynicism that, rather than rejecting middah k’neged middah altogether, we have the choice to face the tragic irony of upholding a value the Jewish people have not always profited from… and to laugh. To trudge onwards despite devastation — made lighter by a sense of cynically Jewish humor — and to still maintain values as good-natured as Jewish karma is, to me, perhaps the most Jewish act of all.

As a great example of this valiant principle, the Baudelaire siblings give us plenty to learn from. I know electing modern-day founding fathers and mothers isn’t a thing, but if it ever is, my ballot goes out to Sunny, Klaus and Violet.

Header image from the cover of A Series of Unfortunate Events: The End by Lemony Snicket.