Editor’s note: The author of this piece serves as president of the board of Meta-Phys Ed, the theater company producing “Banality of Evil” this month at the Brick Theater in Brooklyn.

Scissors, check. Waxed hemp string, check. Printed packet of tekhines (Yiddish prayers), check. I am packing my bag for a pilgrimage upstate with two dear friends. I’ve invited them to accompany me to the cemetery that sits in the center of the campus of Bard College, located in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. It is just over 100 miles north of my Brooklyn apartment, but I suspect it will take us at least three hours to get there on a Monday afternoon. I put some coffee in my thermos, pick up a few bagel sandwiches and head to our meeting point.

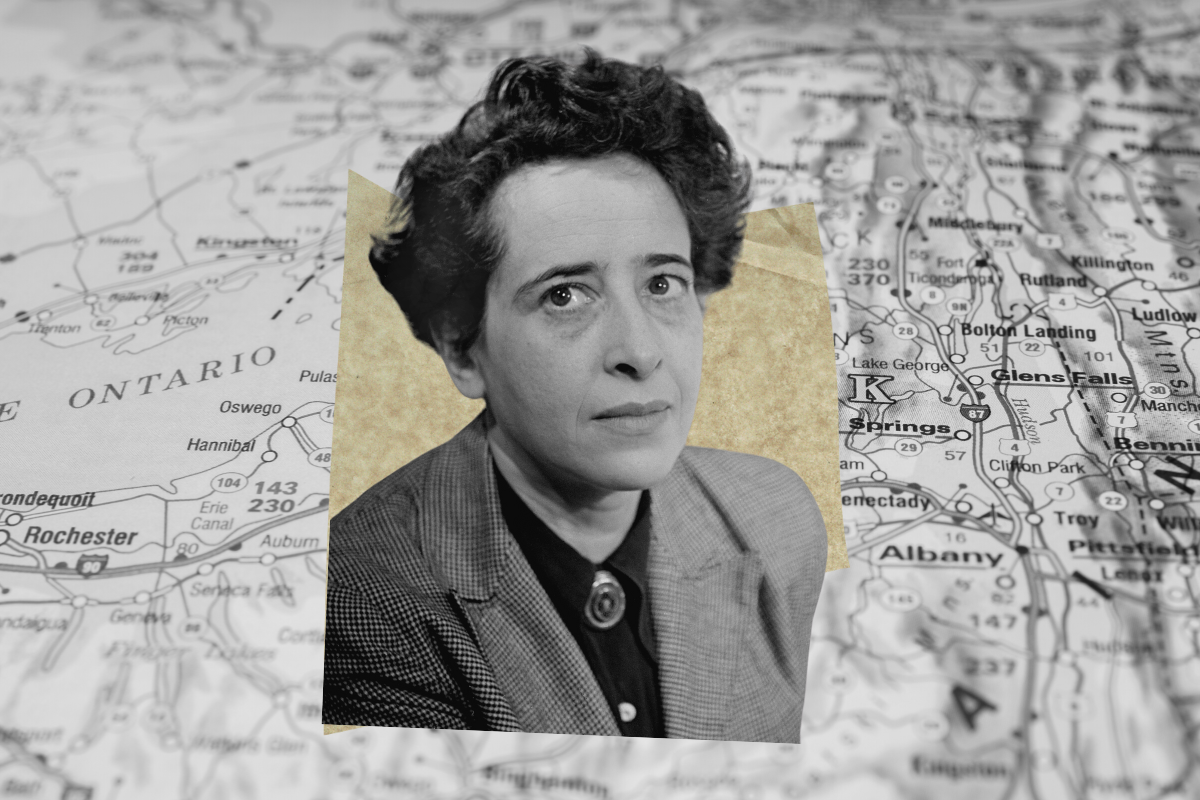

It’s a federal holiday, President’s day. I haven’t always desired to spend my holidays in cemeteries. But in recent years, I have been drawn to them as a place of ritual, curiosity and authentic Jewish magic. Though I am not a Yiddish speaker, I’ve carried my great-grandmother Bubbie Sarah’s prayer book of tekhines for more than a decade. I have been curious about these prayers — published in 1910 Vilna, Lithuania, 650 miles northwest of the shtetl where she grew up in Pochiav, Russia in 1895 — and often find myself wondering when she would have acquired this book, since it was in 1906 that she immigrated to the United States and 1911 when she married her first husband. It’s a question, like so many others, that I may never receive clarity on, but I’ll always have the physical object to connect me with my lineage. Today, I pack this sacred object carefully in a plastic bag. We are traveling 100 miles to the grave of Hannah Arendt.

I recently became intrigued with Arendt when a dear friend, Jesse Freedman, began his project of putting on a play of her 1963 book “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.” Her writing and her life story struck me as prophetic, her words relevant to the resurgence of antisemitism.

Holocaust perpetrator Adolf Eichmann was in hiding in Buenos Aires, Argentina when, in May 1960, Israeli agents abducted him at a bus stop and brought him to Jerusalem to be put on trial. Drawing criticism from the United Nations, Israeli authorities moved forward with the trial, choosing to televise internationally, so that the whole world would bear witness to the atrocities of the Holocaust.

Hannah Arendt, a Holocaust survivor and philosopher turned political theorist born in 1906, the same year as Eichmann, swiftly pitched William Shawn, editor of the New Yorker. Shawn accepted her offer to report on the trial. Arendt’s Feb. 8, 1963 article, “Eichmann in Jerusalem” (along with part two) became the basis for her book of the same name, bearing the subtitle: “A Report on the Banality of Evil.”

Arendt traveled from her home in New York to Jerusalem to bear witness to the trial, which began on April 11, 1961. That December, Eichmann was found guilty on all accounts and was hanged on June 1, 1962 at Ramla Prison, which remains, to date, Israel’s only judicial execution.

As I read Arendt’s words this past November and December, I strongly sensed that I wanted to talk to her. To tell her about what life was like in 2023. Like many prophets, she would be devastated that so many of her predictions came true — she would be disturbed to know that so much of what plagued the Jewish people in 1963 is still causing us suffering. And yet, I had a sense that if her spirit could travel to 2024, she would want to know that we are telling her story. Her spirit called to me. When a quick Google search revealed that her burial site was only 100 miles away, I knew I had to visit her — and, I knew that I needed to bring some string.

In February 2021, I participated in a Zoom course with Rabbi Noam Lerman called “Tkhines: Yiddish Yearnings of Women and Gender-Non-Conforming People.” We learned prayers and practices for measuring either the burial site or an object of a beloved ancestor. That August, I participated in a candle-making activity with Annabel Gottfried Cohen, a historian of women’s shtetl rituals who had just arrived in New York from France for her studies. As someone who grew up with the Irish name “Chandler,” I was thrilled for the opportunity to combine my love of ritual and passion for candle making.

Then in November 2021, when my family finally gathered for my grandmother’s unveiling — which had been postponed due to the COVID lockdown — I knew I wanted to try out this ritual of feldmestn (grave measuring). As we traced the outline of her burial site, I taught some of the Yiddish prayers to my siblings, mother, aunts, and cousins. We then made candles from this wick, saying the prayers that called upon the aspects of my grandmother that we wanted to hold onto as we lit the wicks. I found these rituals comforting and inspiring; it was an activity that brought deeper meaning to visiting a grave and also connected me with the others who longed to hold onto her essence.

In the summer of 2022, Lerman, Cohen and I gathered a few dozen individuals at Mt. Carmel Cemetery to sing tekhines and measure the grave of author Sholem Aleichem and his comrades in the Workers Circle section of the cemetery. Since that day, we have continued to bring together individuals to teach and practice this ritual. While for decades the practice of feldmestn (grave measuring) has faded from memory and been missing from Jewish practices, through our collaboration we are working to revive it as a living accessible ritual.

So on this Monday in February 2024, Cohen and I travel with singer and multi-instrumentalist Éléonore Weill to Bard, to measure Arendt’s grave and converse with her. After singing Daniel Kahn’s all-too-apt song “Dumai/Think” (“I carry in my heart a dream / A flag of peace & a land redeemed”), we measure the perimeter of her grave, as well as her second husband Heinrich Blücher. We use the language of tekhines to call on her, being careful to limit theological references, since we know she was an atheist. We thank her for her courage to travel, to write, to advocate for the stateless. We tell her about the play and let her know she is invited to attend, if she so desires. Each time our voices pause, a large tree just behind her grave creaks loudly.

I feel her spirit, her healthy skepticism and her tenacity. I thank her for it all.

And each time I light a candle I made with this wick, I am calling her spirit into our world.