Growing up, Rosh Hashanah was a benign holiday for me. Apples and honey, food and family. That is, until my brother was diagnosed with cancer the summer before my senior year of high school.

During the first week back at school that year, I was asked to deliver a d’var Torah on Rosh Hashanah. I wracked my brain trying to remember the heroes and villains of the Rosh Hashanah story, and eventually had to check out a library book to learn more. To my surprise, I found that Rosh Hashanah isn’t a holiday commemorating any event in Jewish history. It’s a life cycle holiday. It’s about us and our lives, today. It’s about life, and by extension, death. The blast of the shofar is a daily alarm to wake us up from passivity in our lives, we listen to the Unetaneh Tokef in synagogue to remind us of our mortality, and we eat round challah to symbolize the circularity of life. The whole point of Rosh Hashanah, I learned, is to inspire us to live meaningfully by reminding us that we are alive, and that we won’t always be.

Eight years have passed since I gave a speech to my high school comparing a shofar blast to a cancer diagnosis. Two years have passed since I last saw my brother. He died a month after his 25th birthday.

As a newly minted 25 year old myself, I am more aware of my mortality right now than ever, and as Rosh Hashanah creeps up this year, I feel like shouting, “I KNOW.” I don’t need to hear the shofar. I don’t want to eat the challah. I don’t need the reminder. I am living Rosh Hashanah every day.

In learning to live with grief, I’ve found comfort in talking with friends and relatives who have faced similar loss. In particular, I thought my grandma and I might be able to connect about our grief, since she lost her older sister to cancer when she was about my age. For three years, we’ve gotten close as we spent countless hours together to create a cookbook filled with recipes and memories from her ancestral Iraq. I knew that her sister had died, but until I lost my own sibling, I never thought to ask her what that felt like.

My grandma was 17 years old in 1963, when she finally had enough with an Iraq that most Jews had already deserted. Her family wouldn’t let her leave without a husband, and they weren’t ready to go themselves, stubbornly refusing to relinquish their roots in the country. My grandmother hastily promised herself to my grandfather, and made it onto the last legal flight to ever take a Jew out of Iraq.

My dad was born, American, one year later. My grandma was a mother of three by the time she was 23, and when her sister died a couple years later, she took in her nieces. My grandma was a mother of five before she was 30.

When I finally asked what her grief felt like, she shrugged off my question. At first I interpreted her shortness as avoidance; my grandma understandably brushes off a lot of questions about those hard years. But the more I think about the weight on her shoulders as a teenage immigrant with five mouths to feed and no family to support her, I wonder — between financial stress, keeping food on the table, school pick ups and drop offs — did she even have the time to think about her dead sister? To feel her loss?

As a woman in a society that encourages my independence, in which I have never experienced life altering antisemitism and in which my family is free to be together, I have more privilege in grieving my sibling than my grandma ever had. I can sit and cry for hours, and I do. I can tell the people that depend on me — my coworkers and friends — that I need to take a sick day for my mental health, and I do. My grandma and I both lost siblings, but our experiences of loss have been completely different because of our circumstances.

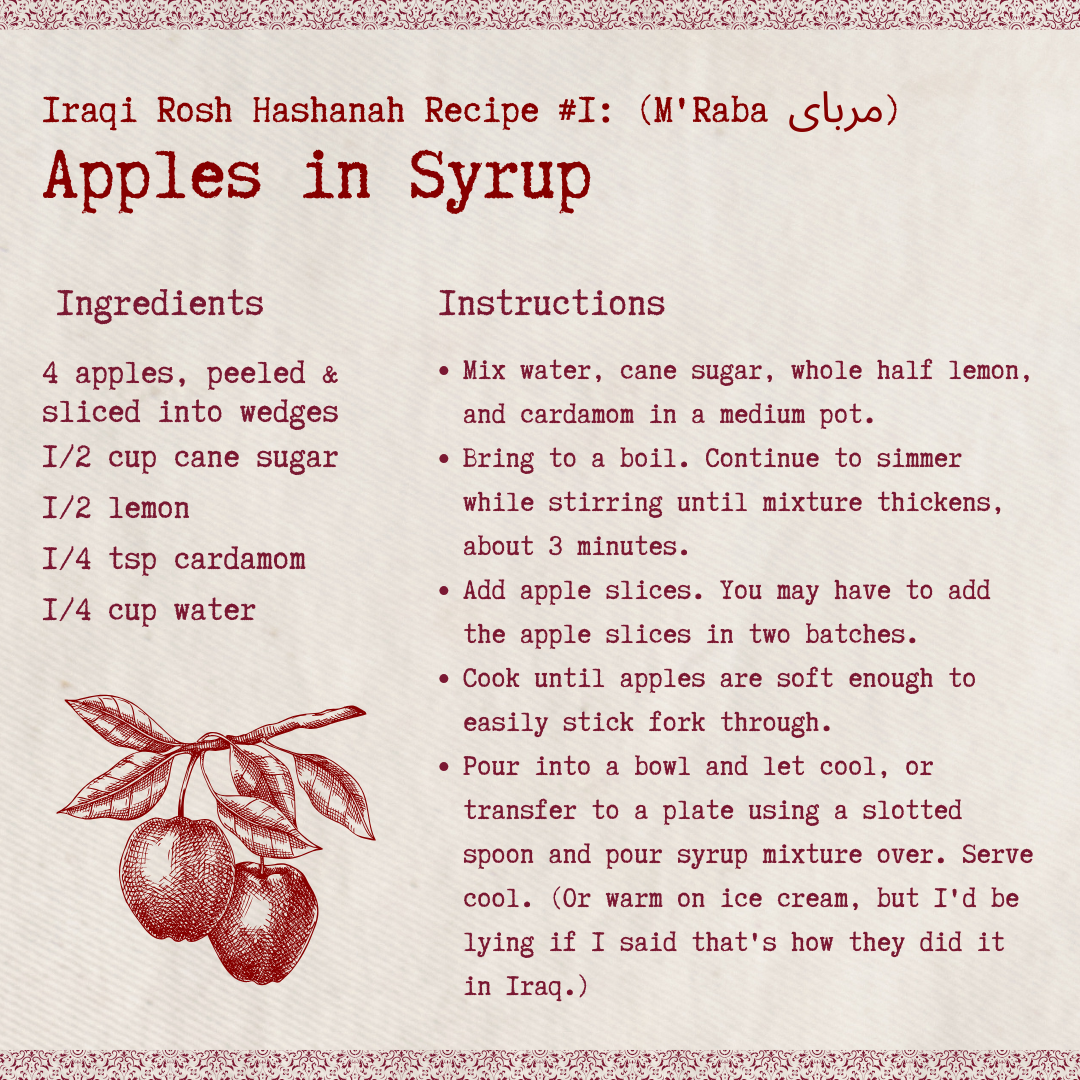

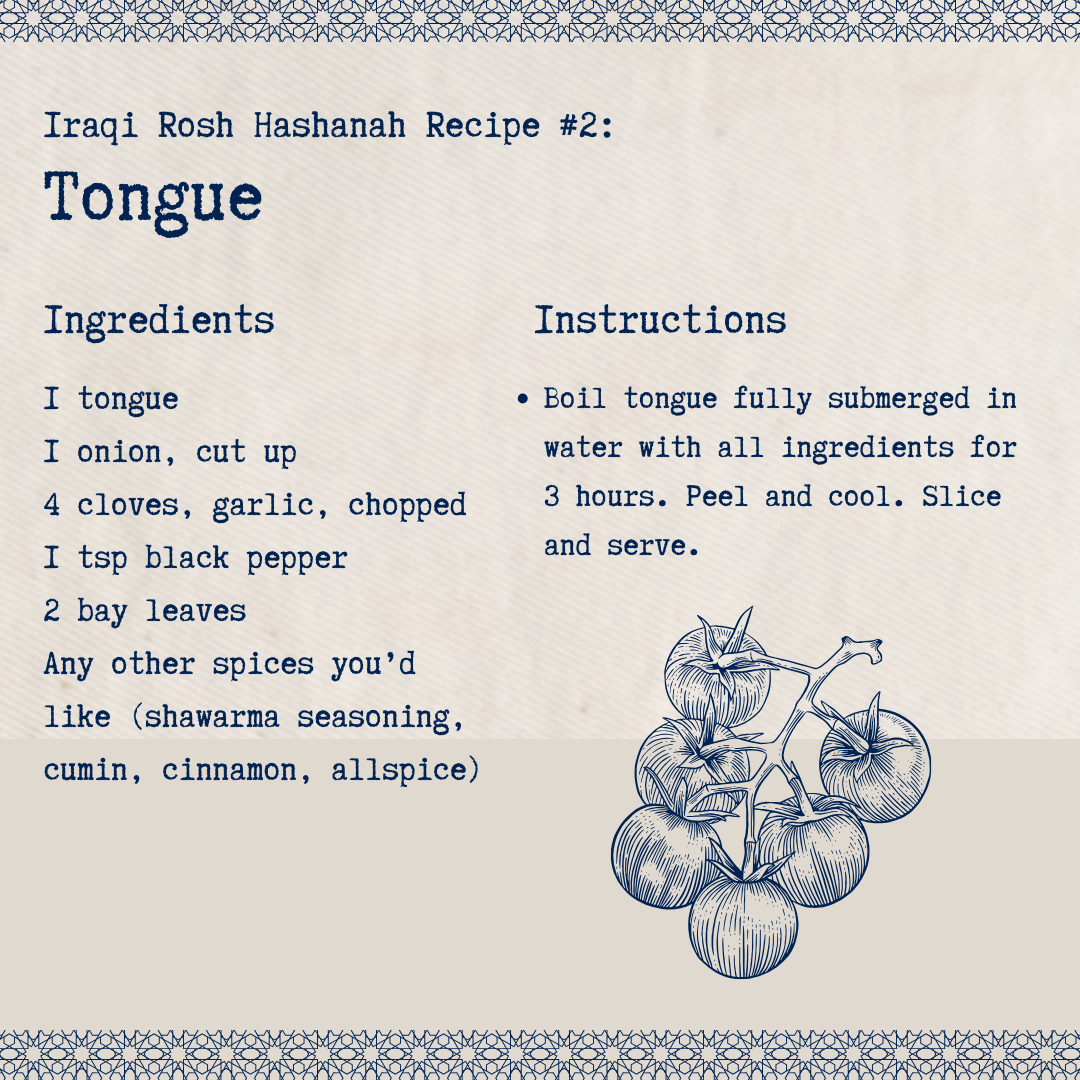

Though my grandma hasn’t, and maybe can’t, relate with me over loss, she does let me into her world through food. This Rosh Hashanah, I am hosting my own traditional Iraqi seder for the first time and I’ll be using her recipes to represent the holiday’s signature reminders of life’s sweetness and death’s inevitability. For sweetness, I’ll be making the Iraqi version of apples and honey, which are more of an apple preserve (recipe below). And for the mortality reminder, I’ll have tongue on my table in addition to the more commonly known fish head, (recipe & link to candy tongue* also below). Sharing recipes for this particular holiday may be the closest we ever get to talking about our grief.

By hosting my own seder, I am stepping through the kitchen and into my history at a time when the circularity of life feels so potent, the curtain separating the worlds of the dead and the living so thin, both in my personal life and on the Jewish calendar.

Rosh Hashanah will always be meaningful for me now; it has connected me to my grief, and through cooking Iraqi recipes, it has connected me to my grandmother’s too. There’s something awfully circular about these generations of layered loss. As reluctant as I am to eat the round challah this year, I understand more profoundly than ever why we do it.

Recipes