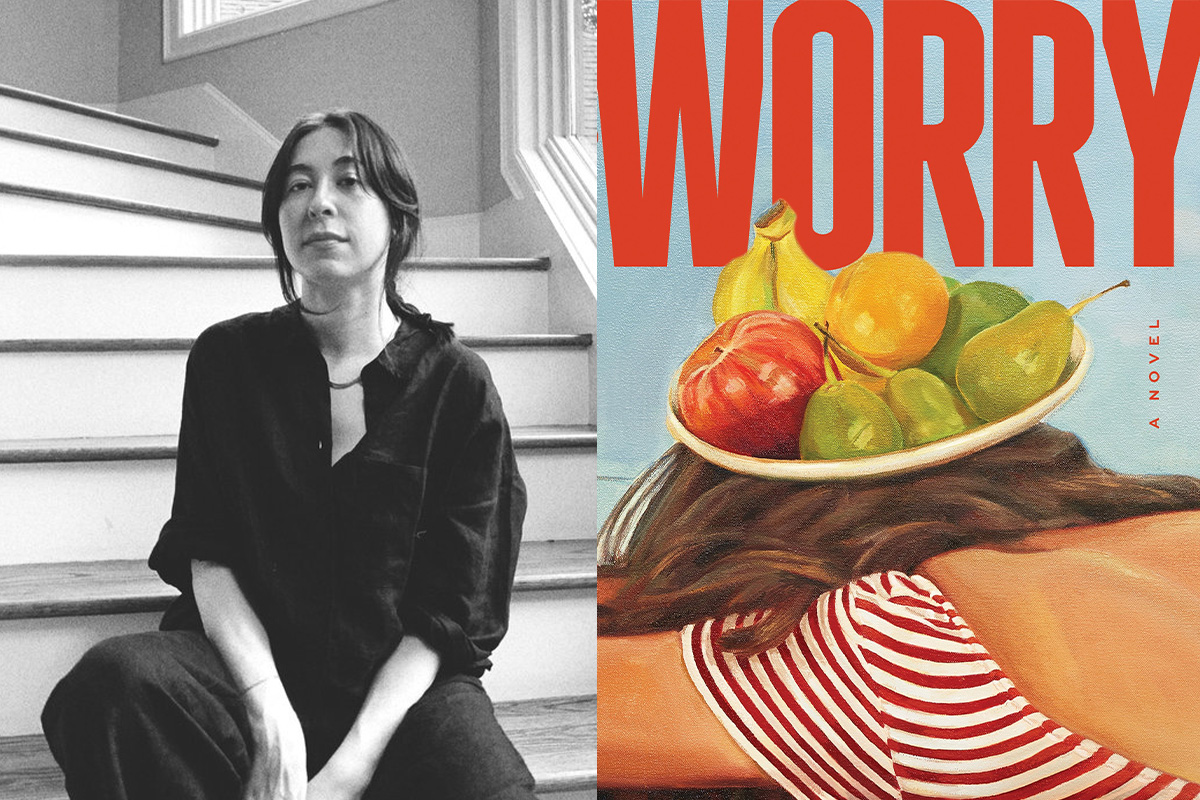

It’s hard to know where to begin with praise for “Worry,” the debut novel of Jewish writer Alexandra Tanner. The New York Times Book Review called it “A Fabulous Comic Novel of Young Adult Angst.” Nylon said, “‘Worry’ is exacting and hilarious, the startling, familiar shock of seeing your own slightly warped face reflected back to you when your iPhone dies from hours of scrolling.” And author Ruth Madievsky, hot off the success of her own debut novel, lauded, “‘Worry’ homes all the trappings of our times that have nowhere else to go: tradwife influencers, Jewish survivor guilt, the boy who threatened to kill you in seventh grade and is now organizing your high school reunion.”

Of course, I agree. But to describe it in terms that would more resonate with the book’s own characters, let me return to something I’ve already said and will definitely keep saying for awhile: “Worry” is a must-read for Hot Jewish It Girls.

The novel follows Jules and Poppy Gold, two Jewish sisters whose joint spiral (the opposite of a joint slay) reflects the eerie precarity of modern life. “Worry” begins as Poppy, a directionless 20-something healing from a suicide attempt, comes to live with her also directionless 20-something sister Jules in Brooklyn. What starts as a short stay quickly snowballs into a year of the pair living together just before the impending COVID-19 pandemic. In that time, the Gold sisters search for meaning in their ever-overlapping lives all while navigating their Jewish identities, Mormon mommy bloggers, hives, a three-legged rescue dog named Amy Klobuchar, a toxic Messianic Jewish mother, uterus problems, a horoscope tech company and more.

I’ve only experienced about one third of what Jules and Poppy experience. Yet “Worry” is the kind of book that made me — and I’m sure will make many other young Jewish people — sit upright and say, “Holy shit, this is about my life.”

I caught up with Alexandra last month via Zoom to chat about “Worry” the book, worry the neurosis, Mormon mommy bloggers and whether she set out to write a novel for Hot Jewish It Girls.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

I read your piece in Jewish Currents about how you, like Jules, follow Mormon mommy bloggers. So first things first: How are the mommies? And are you still keeping up with them?

I’m done. I’m out of the game. I think like the sort of mom-ification of Instagram and that whole oversharing, using your children as props, casual radicalization is still out there. But yeah, I can’t look at them anymore. I’m done.

That sounds very healthy.

I deleted my fake account. I stopped messaging them.

I noticed some of the interactions from the book where Jules calls out the mommies for being antisemitic conspiracy theorists are in the article, too. Are Jules’ interactions with the mommies all real interactions you had?

Not all of them are real. But I did have a couple big moments of like, I have to say something to one of them.

I was writing the book already, and I was sort of integrating the mommies into the book. And it just wasn’t scratching the itch of like, I need to tell people about [Mormon mommy bloggers] right now. Because that particular moment [when I wrote the article], I knew it was going to be over and done. After 2020 was over the vaccines were coming out and everyone was going to start talking about the pandemic in a different way. So I felt like OK, I have this one moment to write this one thing. And then the book will be something else. And so I think in the book, there’s a lot more exaggeration. I would sort of take text I had seen online and add to it or change it to make it a little kookier. But I think there’s definitely overlap between those pieces that were running my life at that moment.

I’m proud to have written that this book is for Hot Jewish It Girls. Was that what you intended when you were writing?

I mean, yeah. My relationship to Judaism has become a bigger part of my life as I’ve grown older and had all these new experiences. I wanted to write a book that explored that and that looked at Jewish humor and Jewish values and abandoning Jewish values and having two siblings explore what it is to be a Jewish girl, a hot Jewish girl, a bad Jew. I wanted all of that to be in there.

It all really resonated with me. I especially loved those really delicious argument scenes where Poppy and Jules are arguing about Israel in Target or when they’re fighting in the Jewish cemetery. Is there a specific scene or line in the book that is a favorite of yours?

I’m trying to think… the big thing that comes to mind is the ending. I feel like I fought really hard for it and I’m proud of what it does, even though I think it’s potentially confusing or it’s the most mystical part of the book or the part of the book that’s the most lifted out of reality.

You had to fight for it? Did your editor want to do something different?

No, my editor Emily is amazing. She was always like, this is the ending. Let’s do it the way you want to do it. Let’s make it have the maximum impact. But internally, I went through so much of like, should I take it out? Should I put a bow on [the ending]? I had feedback from other readers who were like, “Maybe you should end at the scene earlier? Where they’re happy and are coming together in the moment.” So I pushed hard to make it work and I went through a bunch of different iterations.

I like how it feels unresolved. I have an older sister and for me it makes sense that they don’t have this ending of coming together. I feel like there are always strands left unresolved in sibling relationships.

I think that’s so true of sister, sibling relationships. Every time you sort of get over a hump in your relationship, and you’re like, “OK, we figured this out, we have a plan, we’re going to check in with each other and be there for each other,” there’s always something else that comes in. Sometimes it feels like it comes from outer space, and it disrupts whatever little plan you’ve made for how to get along. I wanted to leave them in the spiral a little bit.

Can you talk a little bit about what Jewish sisterhood or siblinghood means to you?

I come from an interfaith household. Judaism, to me, is about tradition, and the repetition of ritual and showing up for one another. I think that is definitely present in my relationship with my younger sibling, and that questioning of like, “Why are we going through this every year?” Doing the same thing over and over, but finding beauty in that and finding newness in it. That aspect of Judaism, to me, translates a lot to what it takes to build and sustain a relationship with a sibling, and what it means to keep a sibling relationship, which is a huge, important relationship at the center of your life. It often feels like, “Why do we have to get on the phone every single day?” But then when you get on the phone every single day, something amazing breaks open and happens. And you rediscover who you are to each other.

That’s beautiful. And for Jules and Poppy it helps that they have each other as allies against their mother. On that note, why is Messianic Judaism a part of “Worry,” too?

I don’t know, man. To me, religion is like a tool of oppression and so I find so much beauty and possibility in the values of Judaism. And I see this commercialization of Judaism and all these different permutations of it — like Kabbalah had this whole movement, there was this big Kabbalah center in Boca and now there’s this Messianic thing where pieces of Judaism become available to anyone who wants to slice. You can do a harvest meal and that’s the transformation of Sukkot or the High Holy Days. It’s just very confusing to me to have this part and parcel of all these different traditions and religions and sort of mixing at your convenience. And yeah, I don’t know. It’s just funny. It’s funny to me that I’m talking about it. It’s serious, but I also think it speaks to this American confusion about who we are and where we come from and trying constantly to create these new traditions to live in that don’t really make any sense.

Something that stuck out to me and really made me laugh was when Jules’ and Poppy’s mom sends them a Jews for Jesus-y email and it says “THE BEST IS YET TO COME.” And Jules’ response is, “I’ve never known a Jew who thinks this way.”

Never, never. Can’t imagine thinking like that. I guess that’s like, what Judaism to me is. It’s a set of cultural responses that come from this long legacy that you don’t even really understand as a part of you until you sort of come up against something where you’re like, “Oh my God, what is that?” and you realize that you are part of this big culture. You are part of this perspective on the world that’s really different from most of the world.

Was it cathartic for you to write a novel about anxiety and worry?

Yes. I drew a lot on my own mental health stuff and mental health stuff in my family. It has allowed me to see myself a little bit as a character, and to see my neuroses and my problems as the problems of someone who is separate from me, but who I care for. I’m able to catch myself a little bit better now. Make fun of myself a little bit more. I didn’t set out to do that. But that’s sort of what happens when you create this maze for someone who’s very much like you. You want to help them through it, instead of trapping them in it.

It taught me a lot about making a character — that as soon as you put a piece of yourself or a piece of your sibling or piece of your parent on the page, you might think you’re rendering life. But something transforms and they sort of carry themselves away, and that’s cool.

That sounds very golem-like.

Yeah, absolutely.

Has your family read the book?

They have. They’re fans. My parents have goldendoodles and my mom keeps taking pictures of the goldendoodles posed while reading the book with little glasses on.

That’s so funny. There’s this idea in my mind that goldendoodles are the most Jewish dog.

They are! Unequivocally.

In your view, why does worry or anxiety feel like such a Jewish emotion?

That’s a hard question for me to answer because everyone’s relationship to Judaism is so different and everyone’s coming at it from a really unique blend of familial, cultural, personal. For me, the religious aspect of Judaism hasn’t been a big part of my life. I grew up in South Florida in a very Jewish area and I was always the least culturally Jewish of my peers. I didn’t have a bat mitzvah, we sort of were very loosey goosey with tradition and holidays. I never felt super, super Jewish. And then I went to college. I went to school at UF in Gainesville, a big southern university, and all of a sudden I had a roommate who had never met a Jewish person and was asking me questions about being Jewish. I wouldn’t say there was a spotlight on me because there’s a big Jewish community at UF as well. But it was just in that little room that I was like, “Oh my God, I’ve never met someone who looks at my background, my culture like this.”

I think from that point on, I started thinking of myself as more Jewish and learning more about Judaism. So, I think [my Jewish worry] comes from that place of feeling like, “Oh, I’m sort of other in a way I didn’t know I was.” I think even if you have an experience of safety, privilege, whatever, as I had, there’s still always that moment. So anxiety and neuroses and laughing at anxiety and neuroses comes from reconciling a feeling of otherness with a feeling of “Oh, but I have such a strong cultural heritage that I might not even have known was so strong within me until this moment.” What do you think about Judaism and neuroses and anxiety?

It’s funny because obviously, there’s the intergenerational trauma of it all. But, for context, my mom converted to Judaism in the ‘90s, before I was born, because she wanted to. And my dad is Christian, so I grew up in an interfaith household without Jewish family or ancestry. But I’m still so neurotic and so anxious, and I think that’s because I grew up going to synagogue and Jewish youth groups and was so steeped in Jewish life. But I totally agree with you. I think what is so Jewish about anxiety and worry is the ability to kind of turn it on its head and laugh about it and the ability to recognize that you are being neurotic, but also not being able to stop.

Have you seen the movie “A Serious Man”?

Yeah.

It’s one of my favorite movies of all time. It was huge for me in speaking about this sense of worry and anxiety and ineffability. Where does it come from? I think all the time of the scene where he’s watching his neighbors, whom he calls “the goys,” and they’re coming back from a hunting trip. He has to ask the neighbor a question about the property line, and the neighbor is unstrapping this big deer from the top of this car, and he’s like, “What do you have to ask me?” It’s just this moment of like, “Oh my God, we are on completely different planes and trying to get into it.” And why hunting? Why is that American and goyische? That moment unlocked so much for me.

There are so many kinds of anxiety in “Worry,” like health anxiety, Jewish anxiety, relationship stuff, etc. Do you have a favorite flavor of anxiety?

I’m trying to think about how to interpret “favorite.” Because there’s intrusive thoughts, there’s food stuff… my pet anxiety is food safety. I never want to know how the sausage is made.

Totally.

I need to know that everything has not been in that four-hour danger zone out of the fridge. That’s my number one thing that I know I should find ways to get over it, but it’s my little pet thing that I can’t ever get over.

My partner also has that anxiety and we’ve talked about it. I’m always like, “Is there anything I can do to help you conquer this?” And she’s like, “No, I’m sorry, but you’ll have to deal with this forever.”

If I open a jar of mayo I’m always asking my partner, “Can you just smell this? Can you just take a little taste just to make sure it’s still good?”

My partner has started to set boundaries with herself where she’s like, “OK, I’m going to be anxious about this, but you can’t validate the intrusive thought by responding to it.” Because she used to ask me to affirm that her intrusive thoughts weren’t true. The other day, we left our dinner outside of the fridge for a bit and she was like, “Are you sure that if we eat this tomorrow, it’s not going to be poison and kill us?” And then I paused and she was like, “Oh wait, I actually heard it that time.”

Right, right. Not asking for validation of the thought is a huge part of stopping the thoughts. It seems cruel that what you have to do to yourself is to isolate yourself with the thought.

I think in the book, part of Jules’ problem is she’s just incapable of doing that and not needing the affirmation to move forward.

Yeah, a sibling is the perfect person out there for that worry. They’re either gonna feed it or they’re gonna make you feel bad for having it.